In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue. ~Children’s rhyme

If you count historical success by cities and districts, controversy and confused school children, Christopher Columbus has the edge.

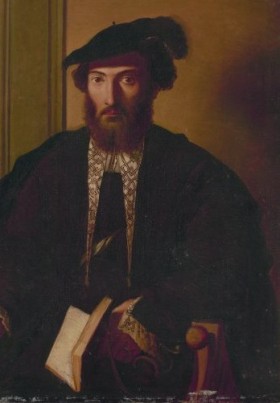

But if you liken it in square miles, late bloomer Amerigo Vespucci (1454-1512) wins by two continents.

Why aren’t the Americas named for Columbus?

Because Vespucci took a leap of imagination and recognized the obvious.

Venus and Mundus Novus

Amerigo Vespucci was born in Florence to a noble family. His Uncle Georgio Antonio, a Dominican friar, gave him an outstanding education in Greek, Latin, astronomy, cosmography, mathematics and natural philosophy. Amerigo also acquired advanced navigation skills, surprising since Florence is landlocked. But then, most towns in Italy lie less than 50 miles from the sea, and trade equaled wealth.

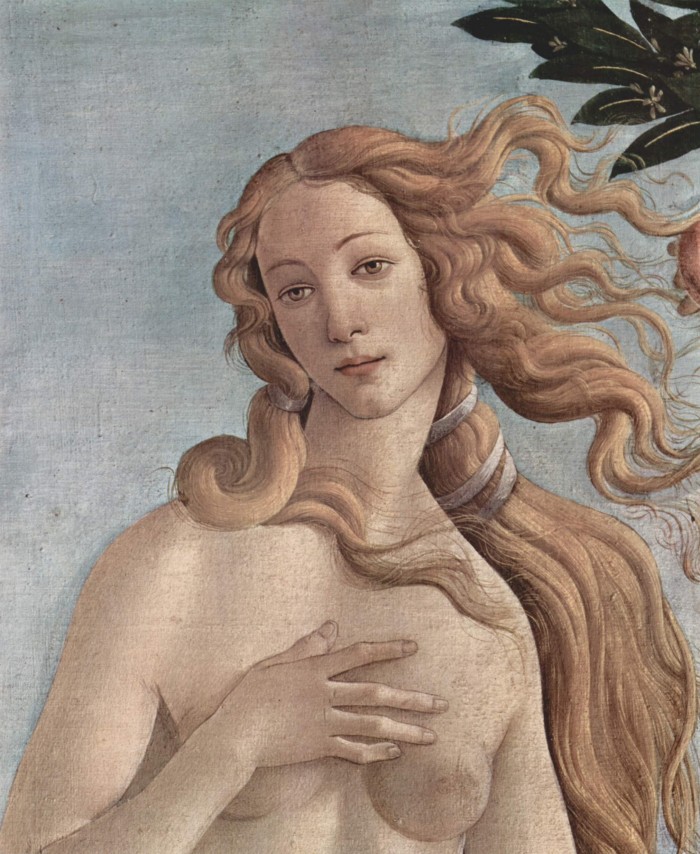

After Amerigo completed his studies, his Uncle Guido Antonio, ambassador to the court of Louis XI, took him to Paris and taught him diplomacy. One of Amerigo’s distant cousins, Simonetta Vespucci, was a Renaissance supermodel and Botticelli’s muse.

But in 1483, Amerigo’s father died and the family fell on hard times. Amerigo entered the Medici household as a steward.

(The Medici were unofficial rulers of Florence and most of Italy, only rivaled by the Borgias, anti-heroes of Showtime’s TV series.)

Amerigo rose through the Medici ranks. He oversaw their banking operations in Seville and directed a firm that outfitted seafaring expeditions. He supplied the third and fourth voyages of Christopher Columbus and the two became good friends.

Amerigo must have sat in his “office” overlooking the port at Seville, watching the ships come and go, come and go, returning with gold, spices and exotic foods. Logging goods, comparing destinations, assuring his investors got their cut.

Only to realize, over time, that ships from the east brought back familiar exotic items—cinnamon and pepper, ebony, sugar and silk.

But Columbus’s ships carried bizarre fare—potatoes, tomatoes and corn, chili peppers, cocoa, and coffee beans to boil into noxious brews.

By 1499, at age 45, Amerigo decided that Columbus had clearly not found a route to India. He obtained three ships from King Ferdinand of Spain and voyaged South America at least twice over the next few years.

As Amerigo sailed down the coast of Brazil, he knew, from years of navigation study, it was too far to the south to be India. He wrote a letter to his friend and backer, Lorenzo de Medici, declaring the continent a Mundus Novus (“New World”).

Lorenzo published the letter, which became a sensation. The idea of a New World ignited the popular imagination.

But it placed Amerigo at odds with his old friend Columbus, who still maintained that the lands were part of Asia.

How America Got Her Name

Martin Waldseemuller, a German mapmaker, championed Amerigo’s Mundus Novus. In 1507, he produced a large 12-panel wall map in which a new continent named America appeared for the first time. He wrote:

I do not see what right any one would have to object to calling this part after Americus, who discovered it and who is a man of intelligence…that is, the Land of Americus, or America: since both Europa and Asia got their names from women.

Americus is the Latin version of Amerigo. Waldseemuller used the feminine because in ancient Greece and Rome, female deities traditionally protected places. Somehow the name caught on survived the centuries, despite a few attempts to change it.

King Ferdinand created a new position for Amerigo, Pilot Major (pilato mayor) of Spain. Amerigo trained up the next generation of explorers and encouraged scientific advances in navigation. He discovered a new system for computing longitude and calculated the earth’s circumference within 50 miles.

Despite their differences, he and Columbus stayed friends to the end. But Columbus died a bitter man, locked in a legal battle with Spain for the right to rule his “discoveries” and receive 10% of their profits.

Amerigo, however, explored for the sake of knowledge, recognized a New World, and let it be. He found love and married a Spanish woman, Maria Cerezo, at age 51. They had no children, so perhaps she too was older. He died seven years later, esteemed by his wife, his navigation students, and the King of Spain.

Was that partly because he pursued his earth-shattering idea at age 45, after years of study, hard work and observation, in other words, after acquiring some wisdom?

I like to think so.

Epilogue

In 2003, by the Library of Congress purchased the only known copy of Waldseemuller’s map for $10 million. UNESCO inscribed it in their Memory of the World Register, the first document in the United States to be so honored.

Other tales exist about how America got her name, including one with Welshman Richard Ameryck. You can read them here.