To catch a boy and hold him fast one has only to set the delicate machinery of the wonder-box in him at work.

—Lew Wallace

I.

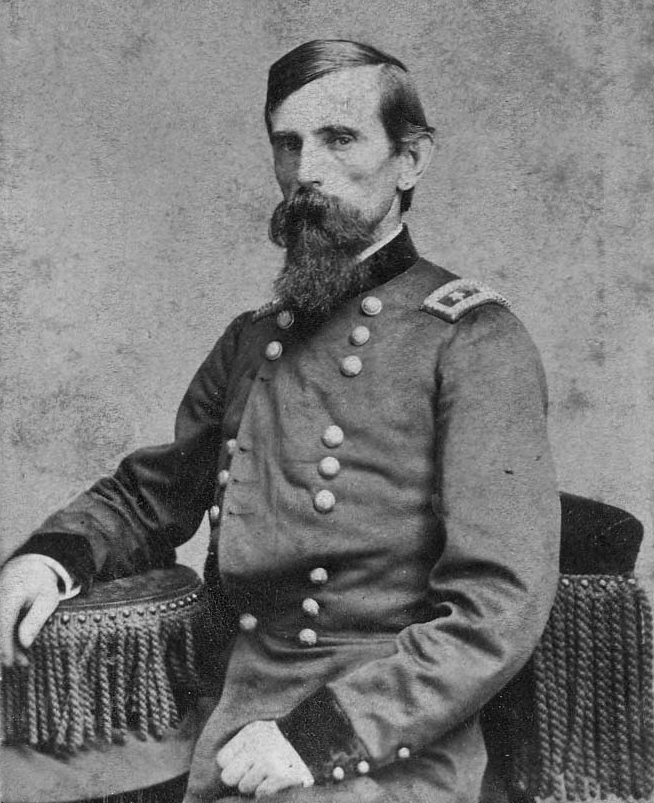

General Lew Wallace, tall upon the back of his stallion Old John, paused to admire the red-gold Virginia countryside.

“What a portrait we’d make,” he thought. “After this war ends, I must pick up a paintbrush again.” He patted Old John’s neck and urged him on. They cantered into the headquarters of Ulysses S. Grant like the legends they’d once been—before the Battle of Shiloh.

In his memoirs, Grant would describe the horror of Shiloh thus:

I saw an open field…so covered with dead that it would have been possible to walk across the clearing, in any direction, stepping on dead bodies, without a foot touching the ground.

Shiloh was the Civil War’s first bloodbath, leaving 24,000 men on both sides dead or wounded. President Lincoln demanded an explanation for the slaughter. General Grant needed a scapegoat.

He pointed the finger at Lew Wallace. Wallace and his regiment arrived late to the battle, costing thousands of lives. But historians still debate his reasons and who was at fault.

Now Wallace had famously saved Washington DC from the Confederates. So Grant thought it prudent to show his gratitude. He invited Wallace to his headquarters to talk strategy, carefully skirting Shiloh.

They rode out together and Grant challenged Wallace to a good-natured race. Wallace couldn’t refuse. He also couldn’t beat his commanding officer.

“GO!” The Union soldier dropped his kerchief. Grant took off at full gallop. But Wallace reined in Old John. The stallion’s forelegs rent the sky in frustration.

“Let him out,” Grant yelled back.

“Why the hell not?” Wallace probably thought, not that he believed in Satan or God or their respective domains.

Old John whooshed ahead. After a few miles, Grant stopped the race and offered to buy Old John right there.

“Not for love or money,” Wallace told him. He wouldn’t part with the horse who’d been true to him when Grant had not. Grant’s duplicity around Shiloh would haunt Wallace for the rest of his life. Perhaps he eventually forgave his commander, but he never forgot.

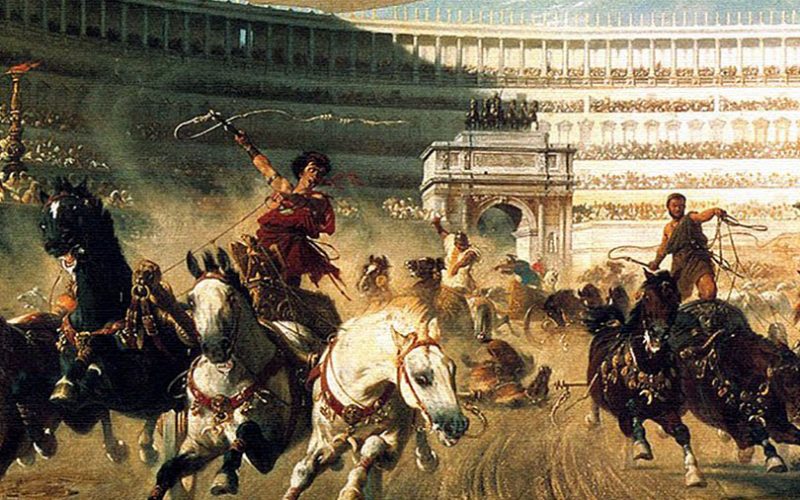

At age 53, Wallace became the late-blooming author of a successful novel. Its climax depicts a visceral race between two former friends—a Jewish prince and the Roman tribune who betrayed him.

Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ made Wallace a celebrity.

How did an agnostic soldier come to write a story of redemption? Even more intriguing, how did writing that story redeem the young artist in Lew Wallace?

II.

In 1827, the year Lew Wallace was born, landlocked Indiana was America’s wild west.

Tecumseh’s defeat at Tippecanoe had opened the land to white settlers. They razed the forests for their cabins and crops, forever changing the Native American’s sacred terrain. Skirmishes between the two cultures worsened. Danger was never far away.

Young Lew, safe in the small town of Covington, Indiana, only saw the romance and adventure. Heroes roamed the land. Davy Crockett and Jim Bowie still lived, and Daniel Boone had lately passed on. Lew decided to follow their footsteps.

One day, age 5, he snuck out the back door and tumbled down to the Wabash River. The ferryman gave him a miniature oar so he could “help” transport passengers. But his mother Esther grew frantic over his disappearances.

The next time, she followed him and watched from behind a tree. After the ferryman assured her of Lew’s safety, Esther wisely left her son to his boat trips and crawfish stalking.

Yet something deeper drove Lew to the river. In his Autobiography, he admitted,

…it had a coaxing power. My fears were soothed, and I went and, as it were, laid my hand on its mane; and thence we were friends. No one better than Dickens knows what conjurers such things are to imaginative children.

Imagination would become Lew’s manna, the thing that nourished his soul. A good adventure tale captivated him for hours, so Esther taught him to read using his favorites—Ivanhoe, Last of the Mohicans, and The Scottish Chiefs.

But often he begged her to recite the Magi’s story from the Bible. They were explorers after his own heart. Which distant countries did they call home? Did they meet outlaws, Indians, or wild animals while following the star?

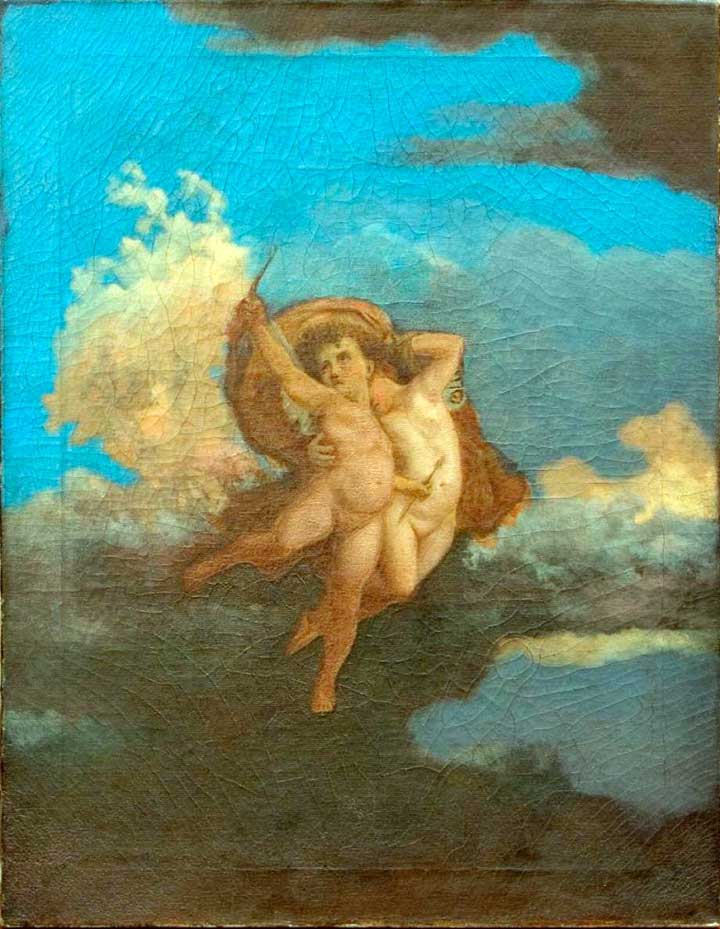

Oil painting by N.C. Wyeth (1919)

When books didn’t quell his wanderlust, Esther dressed him in a petticoat, which, Lew recalled, “shut me in quite effectively.”

(At the time, boys wore skirts until age six or so. Their first pair of breeches signaled a transition to manhood. Returning to petticoats would be humiliating.)

That same year, Chief Black Hawk took up Tecumseh’s cause and declared war on the settlers. Lew’s father David, a Westpoint graduate, came home to drill the local militia.

But all Lew saw was his father’s uniform. “None of the good man’s after honors exalted him in my eyes like that scant garment.” For a five-year-old recently out of skirts, especially one who seldom saw his father, the display must have felt like destiny calling.

When Lew was seven, Esther died suddenly from a virulent form of tuberculosis. By the time Lew’s father received the news they’d buried her. In his Autobiography, Lew reveals his devastation at her death and “the bereavement it so remorsefully inflicted on me.”

Years later, he would name Ben-Hur’s beautiful and compassionate heroine “Esther.”

Lew doesn’t mention how he felt about living with the neighbors while his father served as Indiana’s lieutenant governor. Mostly they let him roam the countryside with his gun and his Memoir of Daniel Boone, so he had few complaints.

A few years later, David Wallace became Indiana’s sixth governor. He finally brought Lew and his two brothers to live with him in Indianapolis. He’d also recently remarried a woman eighteen years his junior.

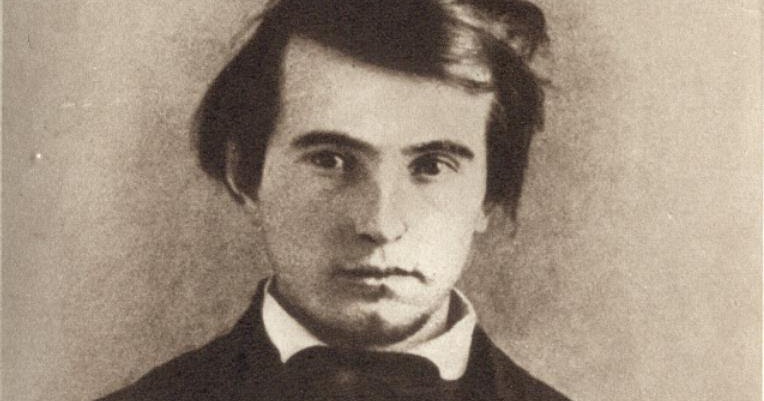

Yet, in the upheaval, Lew discovered a new outlet for his imagination. David Wallace commissioned Jacob Cox to paint his official portrait. Lew “boldly invaded” Cox’s studio and watched him for days.

The painter taught him to grind and mix colors, but that wasn’t enough for Lew. “My fingers itched to try them.” He spirited away some paints to the attic.

There I found myself in want of everything else needful, yet my ingenuity was equal to the trial. For brushes, I plucked hairs from the tail of a dog and tied them to a stick.

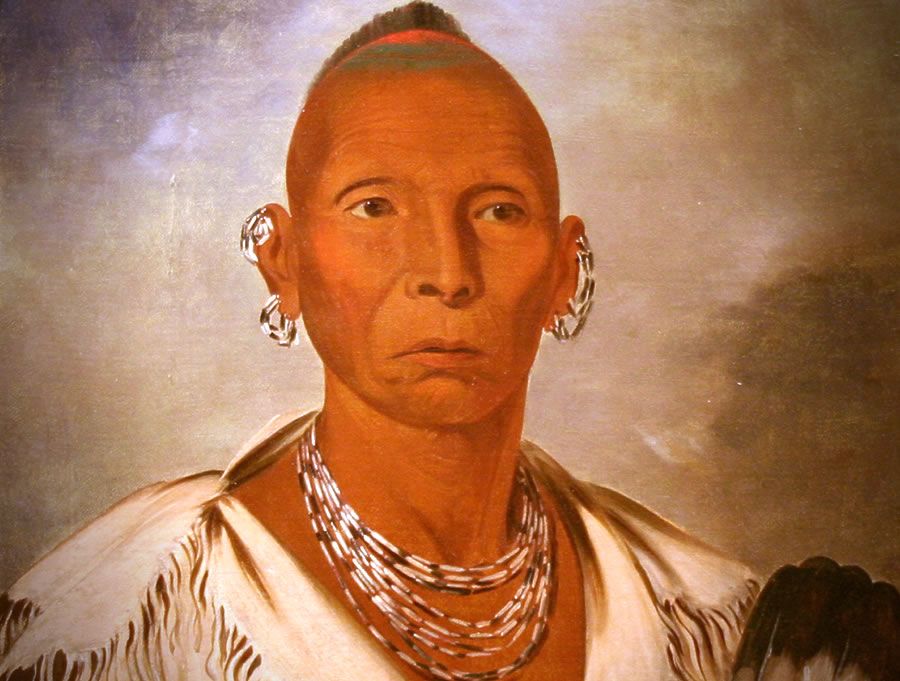

His stepmother discovered his atelier and took Lew’s first painting, a portrait of Chief Black Hawk, to her husband. It was good, David Wallace grudgingly admitted.

But he warned Lew, “You must give up drawing…To give yourself to the pursuit means starvation.” Lew ignored him and often skipped classes to create a new canvas.

Oil painting by George Catlin (1832)

When Lew turned sixteen, David called him to the study and handed him a stack of tuition receipts—evidence of the formal schooling Lew had wasted in the pursuit of art.

“To be a great painter,” David told him, “two things have always been necessary—a people of cultivated taste and then education for the man himself. You have neither.”

He told his son to move out and make his way in the world. Lew clearly idolized his father, for he accepted these harsh words as truth. He recalled,

I resolved to give up the dream. Still it haunts me. At this day even, I cannot look at a great picture without envying its creator the delight he must have had the while it was in evolution.

Lew left home that day and found a job copying court records. The tedium only further inflamed his imagination. “The extinguishment of the beautiful dream left me disconsolate, but not for a great while.” He spent candlelit evenings devouring every tale of romance and adventure he could get his hands on.

Then he borrowed William Prescott’s Conquest of Mexico from his father’s library. A new beautiful dream gripped him. “I would write, and the Conquest of Mexico would be my theme.”

He titled his novel The Fair God: A Tale of the Conquest of Mexico, but he didn’t take the conquerors’ viewpoint. His protagonist was Fernando Cortés Ixtlilxóchitl, the historical great-grandson of an Aztec king. Later he would tell the story of another colonized prince.

Although Lew’s writing passion eased the loss of his painting dream, a quarter century would pass before he finished The Fair God.

III.

After two years in a dead-end job, Lew Wallace craved more.

I felt the impulses of manhood in near approach. The ego in me began to wrestle with the question…what am I to do with myself?

Few paths to manhood existed at the time and art wasn’t one. So Lew, consciously or not, repeated the fateful decision so many young men make—he became a soldier.

After joining a local militia, he marched further down the path to “manhood”—he asked his father to train him as a lawyer.

His two pursuits collided when the Mexican-American War broke out. Lew marched south the day after he sat his bar exam. David Wallace was jubilant. He walked alongside his son’s contingent until it came time for them to part. “Good-bye,” he said, taking Lew’s hand. “Come back a man.” Lew burst into tears.

Lew’s regiment was bivouacked far from the action and lost more men to disease than battle. It didn’t matter. He came home a war veteran.

While visiting his former commanding officer, Henry Lane, he met Susan Elston, Lane’s sister-in-law. “She’s the prettiest girl living,” Lew wrote his brother. The pair quickly fell in love.

Susan was also an accomplished writer who would publish long before her future husband. She gave us the phrase “patter of little feet,” from her popular 1858 poem of the same name.

But her father, a lawyer and a judge, considered Lew something of a wastrel. He might be a veteran, but he’d flunked the bar exam he’d taken before shipping out. How would he support Susan?

So Lew returned to his father’s tutelage and received his license at age 22. He and Susan wed three years later. Their only child, Henry Lane Wallace, arrived within twelve months. The family settled in Susan’s hometown of Crawfordsville, Indiana.

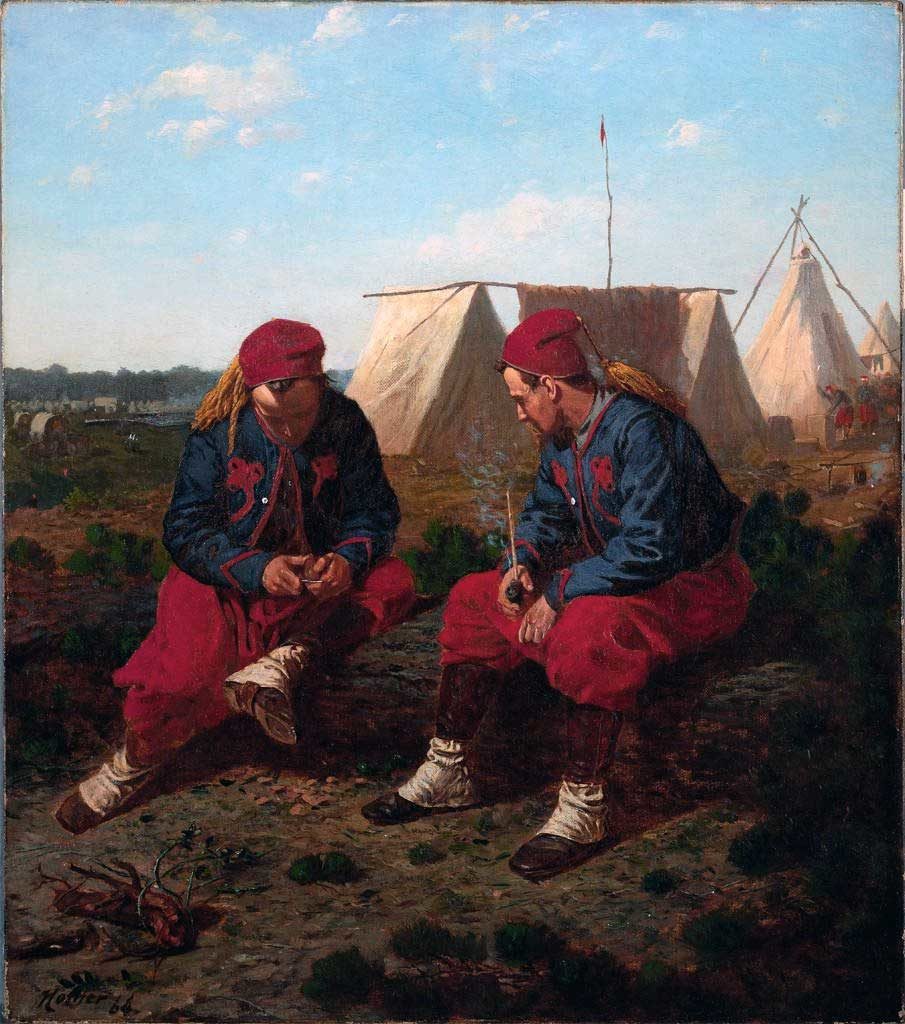

By April 1861, America’s Civil War had started. Lew took command of the Eleventh Indiana Infantry. Ever the romantic, he trained them as Zouaves, a class of French-Algerian light infantry he read about in a magazine.

by Winslow Homer (1864)

The men marched double-time dressed in traditional short jackets and loose pantaloons. They made a rough 20-mile sortie to Romney, Virginia and surprised a stronger Confederate force, which made them media favorites. Lew then joined the war’s western theater under General Ulysses S. Grant.

Success followed success. At age 34, Lew became the Union Army’s youngest major general.

And then—April 6, 1862, the Battle of Shiloh. What happened on the darkest day of Lew Wallace’s life? He and his division arrived late and missed half the battle. Some say he got lost; others, that he’d lost his nerve.

Lew claimed Grant misjudged the enemy’s advance and sent unclear instructions. Grant’s report to Lincoln emphasized Wallace’s “dilatoriness.” Someone in Grant’s office leaked the reports and ruined Lew’s reputation. He was removed from active duty.

Recent scholarship, however, favors Lew’s version. Robert E. Morsberger, writing in the Civil War Times, argues that Ulysses S. Grant’s “hasty and unclear command” steered Lew into the enemy’s main body. The second message from Grant put Lew on track, but he arrived late. Grant denied culpability and blamed Lew for the tragedy.

In the summer of 1864, Lew got his chance at redemption. Grant had left Washington DC largely undefended to pursue bigger stakes. The Confederates took advantage and mounted their advance.

Lew was the only commanding officer within reach. He engaged the Confederates at Monocacy Junction, just 60 miles northwest of the capital, with an unprepared force of around 6,000 men, most of whom had not seen a battle. The Confederates had more than twice as many.

Lew and his men sustained a terrible defeat, but they delayed the Confederates until Grant could send reinforcements. Their sacrifice saved the capital and President Lincoln.

And that’s how General Lew Wallace and his stallion, Old John, found themselves en route to Ulysses S. Grant’s Virginia headquarters to receive his gratitude. They stop to admire the red-gold Virginia countryside.

“What a portrait we’d make,” Lew thinks. “After this war ends, I must pick up a paintbrush again.” It might have been his first inkling that this thing called “manhood” came with serious shortcomings.

A few months later, on April 9, 1865, the Civil War ended. Five days after that, John Wilkes Booth assassinated President Lincoln.

Lew had no chance to rest or recover from his shock. President Johnson called on his legal skills to oversee the trial of the Lincoln conspirators, including Booth. He found all eight suspects guilty.

After that, he convened the war crimes tribunal of Henry Wirz, the commander of a notorious Confederate prisoner of war camp.

Lew returned home having witnessed the worst man could inflict on man. The Shiloh issue remained unsettled, and many still blamed him for the carnage. He no doubt suffered from some form of PTSD.

In the months that followed, Lew did the only thing his wounded psyche would allow—resume painting. He completed portraits of his father-in-law and Henry Lane. He made famous depictions of the trials he oversaw. He also painted a pair of celestial cupids.

He couldn’t portray his father on canvas because David Wallace had passed away right before the Civil War broke out. His death receives a fleeting mention in Lew’s Autobiography, and perhaps that speaks to Lew’s grief. But now he could finally follow his passion.

As his instinctive art therapy evolved, he relived his childhood, his love of literature, his mother’s voice. He recalled her recitation of the Magi’s journey and its “lasting hold upon my imagination.” He started writing again.

At age 46 Lew Wallace completed The Fair God, a novel he’d started before the Mexican-American War.

IV.

The novel sold well, but not well enough to feed Lew’s family. He grudgingly started practicing law again (“that most detestable of occupations,” he now called it). But then his country called.

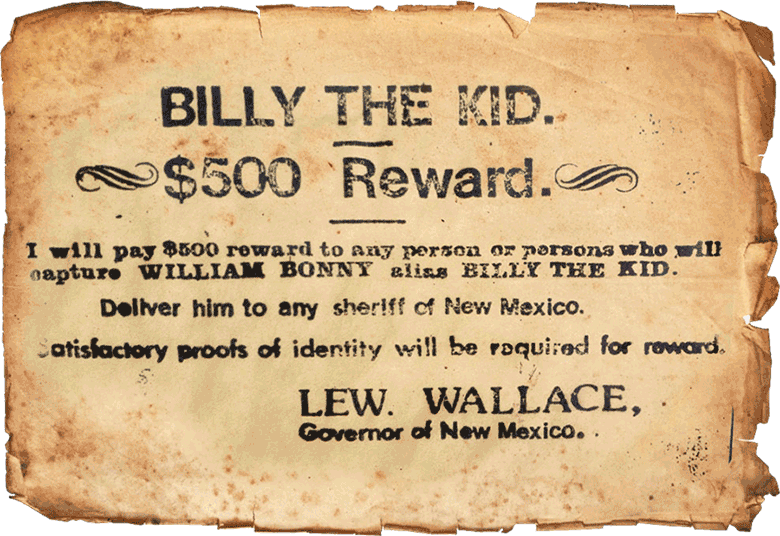

President Rutherford B. Hayes appointed him 11th governor of the New Mexico Territory. Lew’s commission—end the Lincoln County War and bring Billy the Kid to justice.

Wallace made a deal to pardon the Kid in return for his testimony regarding one of the Lincoln County murders, but the district attorney refused to uphold it. The Kid escaped from jail and vowed he would ride into Santa Fe, “hitch my horse in front of the palace, and put a bullet through Lew Wallace.”

Susan shuttered the windows of the Palace of Governors every night, terrified The Kid would spy Lew writing by candlelight and keep his promise.

Before leaving Indiana, Lew had finished a short story about the Magi that ended with the birth of Jesus. As he tossed around ideas for his next book, he realized “viewed purely and professionally as a climax or catastrophe to be written up to…what could be more stupendous than the Crucifixion?”

A chance meeting with a fellow veteran named Robert Ingersoll also influenced his new direction. Ingersoll, the nation’s most famous traveling lecturer, was known as “The Great Atheist” for his compelling arguments against the existence of God.

Until then, Wallace maintained he had “no convictions about God or Christ.” After his talk with Ingersoll, he decided to rectify his ignorance one way or the other.

He’d study Jesus by investigating the region’s religious and political turmoil during his lifetime. Then he’d weave his findings into a novel.

Lew’s short story grew into the first chapters of Ben-Hur, but he had scant time to write in Santa Fe. He complained to Susan (who’d quit the dangerous outpost and returned to Crawfordsville),

I am trying to do four things: First, manage a legislature of most jealous elements; second, take care of an Indian war; third, finish a book; fourth, sell some mines. Can you fancy a greater diversity of occupation?

Finally, cocooned by the adobe walls of the governor’s palace, interrupted by random gunshots in the plaza, he finished his book. In March 1880, he took a train home, picked up Susan, and headed to Harper & Brothers in New York City.

Ever the romantic, Lew had made his fair copy in ecclesiastical purple ink. He personally gave Ben-Hur to Joseph Harper, who called it “the most beautiful manuscript that has ever come into this house. A bold experiment to make Christ a hero that has been often tried and always failed.”

On November 12, 1880, Harper published Ben-Hur: A Story of the Christ. Lew Wallace was 53-years-old.

But only 2,800 copies sold in the first seven months, so Lew took his next assignment. President James Garfield (a fellow veteran) appointed him Minister to the Ottoman Empire, where Lew became the favorite of Sultan Abdul Hamid II.

The position gave him a chance to test his meticulous research for Ben-Hur. At the time, Jerusalem belonged to the Ottoman Empire, so Lew received special permission to travel there. He proudly noted,

At every point of the journey over which I traced his [Ben-Hur’s] steps to Jerusalem, I found the descriptive details true to the existing objects and scenes, and I find no reason for making a single change in the text of the book.

His post ended with the election of President Grover Cleveland. The sultan offered to make Lew representative of Turkey’s interests in Europe, but he declined. Lew and Susan returned to Crawfordsville in 1885.

By 1886, Lew started to earn about $11,000 a year in royalties from Ben-Hur (around $300,000 today).

Finally, at age 58, five years after Ben-Hur was published, Lew Wallace could forego his day jobs.

V.

The pen is mightier than the sword.

—Novelist Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1839)

Lew Wallace lived for another twenty years, long enough to see Ben-Hur become an American phenomenon.

Acclaimed from the pulpits, buoyed by a celebrity following (including President Garfield), Ben-Hur became the bestselling U.S. novel of the 19th century.

In 1899, Lew saw the theatrical version open on Broadway and sell 25,000 tickets per week. He passed away in 1905 at age 77, a rich and very famous man. Susan followed him two years later, after completing his 1000-page Autobiography.

Ben-Hur enjoyed a twenty-year theatrical run. In 1922, the Goldwyn Company purchased its film rights. Their 1925 version cost $3.9 million, making it the most expensive silent film in history.

The 1959 version starring Charlton Heston became one of the most successful movies ever made, winning eleven Academy Awards.

By 1960, renewed interest made Ben-Hur the bestselling novel of all time in the United States. In 2016, MGM released a “re-adaptation” of Ben-Hur.

Lew never stopped writing or painting. But, as he once wrote to Susan,

…it seems now that when I sit down finally in the old man’s gown and slippers, helping the cat to keep the fireplace warm, I shall look back upon Ben-Hur as my best performance…”

Although the words Magi and imagine sound similar, nothing linguistically connects them except through Lew Wallace’s life.

He wrote about the greatest story of romance and adventure ever told. It brought him full circle to his true calling as an artist in the broadest sense. As entrepreneur Seth Godin puts it:

Art is a human act, a generous contribution, something that might not work, and it is intended to change the recipient for the better, often causing a connection to happen…You can enjoy the status quo, or you can make art.

Lew Wallace could have settled for being the 19th century’s Forrest Gump (not a bad gig), but he chose to create art in the evenings while saving a president, convicting assassins and outlaws, and advising a sultan.

Sometimes, like at Shiloh, he failed (according to popular opinion). But he always persevered.

Ben-Hur also challenged the religious status quo. When Joseph Harper received the manuscript, he not only commented on its beauty as a piece of art but its success as a piece of transformative literature.

A bold experiment to make Christ a hero that has been often tried and always failed.

We forget that the man Jesus, called the Christ, was a hero. You don’t have to be a Christian to recognize that. He appears only six times in Ben-Hur, yet his presence permeates the book and changes everyone with whom he connects.

Jesus transforms Judah Ben-Hur’s quest for revenge into the miracle of redemption.

Writing Ben-Hur also changed Lew Wallace. As he later confessed, “Long before I was through with my book, I became a believer in God and Christ.” Yet he never joined a church or denomination. “Not that churches are objectionable to me but simply because my freedom is enjoyable…”

In the end, the imaginative boy who chased romance and adventure became the artist of his story—on his own terms.