Today’s post begins a new midweek series—art, storytelling, and/or inspiration from a good book—to feed your muse.

My muse loves fairy tales, particularly modern ones. Here, author Patricia Nightingale gives us “The Rightness of the Timing: A Modern Ancient Folk Tale.” It’s a bit longer than normal blog fare, but you’ll be so entranced, you won’t even notice.

There was once a young girl who longed to paint. She knew in the depths of her soul, in that place where truth resides, and fairies play with fireflies, that this was her soul’s calling.

Her vocation. The reason she had been born unto this life, in this time.

Every day, in the early mornings, before even the village baker arose and began to heat his ovens and set the bread to rise, she would awaken and walk out to the edge of the village and past, through the narrow gates. Here is where the velvet sky, pierced with stars, met the flat red soil of the earth. And there she would soften her eyes, open her palms to the sky, and wait.

As the sun began to creep over the horizon, turning the sky to azure and the earth to ochre, umber, purple, green and gold, her eyes would fill with tears.

The tears fell at her feet, and over time so moistened the ground that small flowers, no bigger than a pin, began to seed themselves and bloom.

And so it went on for many long years. In this manner, a life was lived. An ordinary life, without fame or fortune or fanfare. The sort of life you never hear about, really. A bit like your life, maybe. Certainly, very much like mine.

Anyway, the girl grew into a woman. She married, went to work, had children. Many years passed, some good and joyful, some filled with sorrow and pain, but most a mixture of the two, for that is the stuff of which ordinary lives are made.

When she was older, her husband decided to leave her and seek his happiness elsewhere. Or perhaps he grew sick and died. The tale is told both ways, and more ways even than these. In some versions, she has no husband at all. In some, she has no children.

But in this telling, her husband leaves, and children, now grown, have children of their own. And because it is often so, they also left the village, to seek their happiness elsewhere. Being thoughtful children, each in their turn asked their mother to come with them.

But always the woman shook her head no. “Thank you, my darling,” she told each of them. “But here I must stay.”

“But why, Mother? There is nothing here in this village. Nothing exciting ever happens. That is why we are leaving. Please, come with us. We will make your life easy, as you have made ours.”

But she was firm. Something deep in her soul knew what no one else did. She could not explain it, but she knew she had to stay. Right there. In the heart of the village where nothing exciting ever happened.

One morning, as she had done for all her life, she arose in the early hours, before even the baker—who was now the baker’s son—was up and stoking the fires for his ovens. She walked to the edge of the village, and through the narrow gates. She softened her eyes and waited for the sun to rise. She opened her palms, and breathed in the cool air.

Fireflies danced around her and the air was sweet. As the black of the night began to fade, the sky turned azure and the earth cloaked itself in ochre, umber, purple, green and gold. Her eyes filled with tears, which streamed down her cheeks and fell to the ground below.

Just then a man came toward her. He came from the east. A stranger. He wore a long robe made of soft green muslin, and leather sandals on his feet. The woman smiled at him, for nothing in his countenance frightened her, or made her want to seek refuge behind the village walls.

The man stopped beside her, and for a long time the two of them stood together, not saying anything, just drinking in the beauty of the place and breathing deeply of the air.

For the air was sweet with the scent of wildflowers, and the spot where they stood, where the woman had stood and wept every morning of her life, wept with sorrow, with joy, for love and beauty, for the earth and sky, wept because she must — this spot was now the center of a beautiful fragrant meadow.

As far as their eyes could see, in every direction, thousands and thousands of flowers bloomed. The hum of bees filled the air. Butterflies and hummingbirds flitted from one nectar-laden blossom to another.

This is what her tears had done. Watered the ground, daily, gently, so that in time the seeds took root in the moistened earth, sprouted and began to grow and bloom. It had taken years, a lifetime in fact. But it was worth it. There was no spot more beautiful on earth to the woman. No place more sacred or sweet.

After a bit, the man turned to her and spoke.

“What a beautiful spot,” he said.

“Yes,” she answered. “It is.”

He nodded. “You know, someone should paint this. Someone who has vision, and who sees it for what it truly is. Someone who knows its history. It is a rare gift, to see what others do not, or cannot, and even more rare when the gift can be made visible and shared with others. Don’t you think so?”

He turned to her and smiled.

“Yes,” she answered again, meeting his eyes. “Yes, I do think so.”

He bowed, and took his leave. She watched him disappear into the distance until he was no taller than one of the wild foxgloves that shot up towards the sky.

The woman walked back through the gates and down the village streets. She went into her small house, and into to the smallest of the rooms, which sat at the very back. This room was so small that no one, not her husband or her children, had ever known it was there.

But she knew. She had known forever.

She opened the door, which had not been opened in many years. It smelt deliciously of old things, leather and must and wood, and old dreams, and a way of seeing that she had kept hidden from others for a long, long time. From the room, she took canvases, her easel and box of paints, paintbrushes, rags, and a three-legged folding stool to sit upon.

There was an old straw hat hanging off the edge of a chair. She took this and shoved it, with a certain determination, upon her graying head. She paused for a moment in the doorway, looking back but feeling no regret.

She left the room, left the house. She did not, this time, bother to lock the door. There was nothing inside anymore which anyone could steal. Nor anything which had to be locked away, kept secret, or hidden.

And then, for the last time, she walked to the edge of the village and through the narrow gates. She walked to the middle of the field. The sun was a yellow circle, high overhead. The air was sweet and the hum of honeybees filled her ears. She set up her easel, placed the canvas upon it, and opened her box of paints.

Tentatively at first, and then with abandon, she dipped her brush in the thick paint, swirling it through the ripe jewel colors. Then she threw back her head and laughed, and with wild grace and a chortle of joy she began to streak the paints across the canvas.

Right across her own soul.

And although many seasons, and many centuries have passed, they say you can see her there still, if you happen to pass by the village at just the right hour.

If you are one of the lucky ones, or the blessed ones. If you are one of those who can see the meadow—which, after all, looks like any other meadow—for what it truly is.

Patricia Nightingale is a poet, novelist, gardener and avid knitter. Her poetry can be found in various places, both in print and on the web, under the name Patricia Frankel.

Her novel, The House on Penny Hill, follows the (often extraordinary) lives of several (otherwise ordinary) women who meet at a knitting circle. It marks the first of a series set in Vermont (and elsewhere).

Patricia’s photo and poetry book, Dreaming Creation: Seven Poems for Seven Days, explores the creation story told in Genesis through a series of dreams she experienced. You can find it on Blurb.

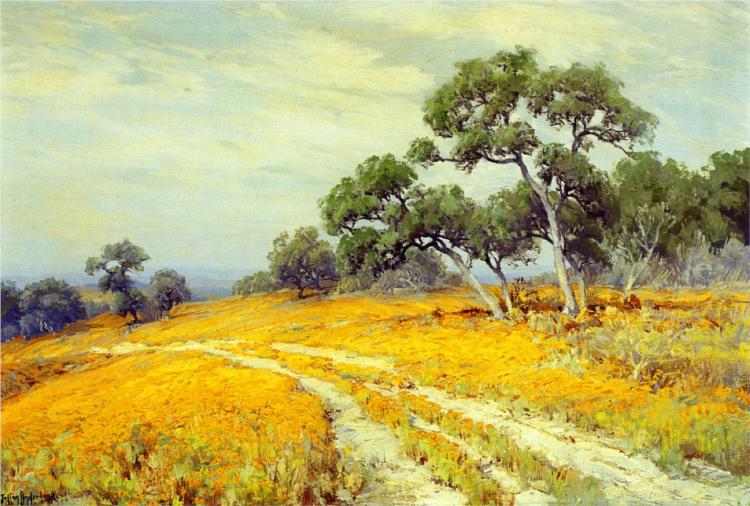

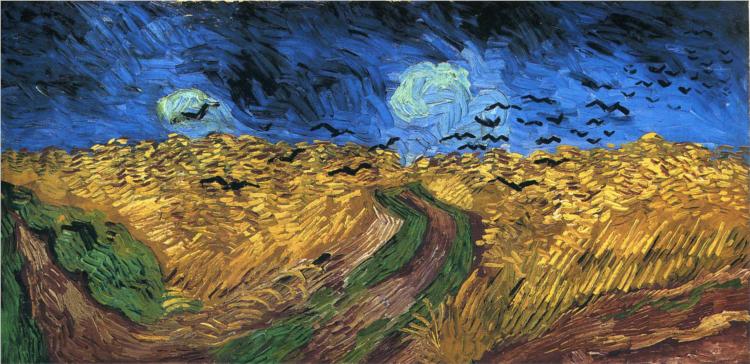

Artwork (via WikiPaintings.org):

- Young Woman Drawing by Marie-Denise Villers (1774-1821)

- The Artist’s Garden at Eragny by Camille Pissarro (1830-1903)

- Landscape With Coreopsis by Robert Julian Onderdonk (1882-1922)

- Wheat Field With Crows by Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890)