On December 3, 1926, Agatha Christie (1890-1976), the famous mystery writer, disappeared.

She kissed her sleeping daughter goodbye, left her secretary a note, and drove into the night. The next morning, her abandoned car was found down a hillside near the manor where her husband Archie was staying with his mistress.

The media went mad. Her husband immediately became suspect. Arthur Conan Doyle, creator Sherlock Holmes, took one of Agatha’s gloves to a psychic to learn if she’d “passed over.”

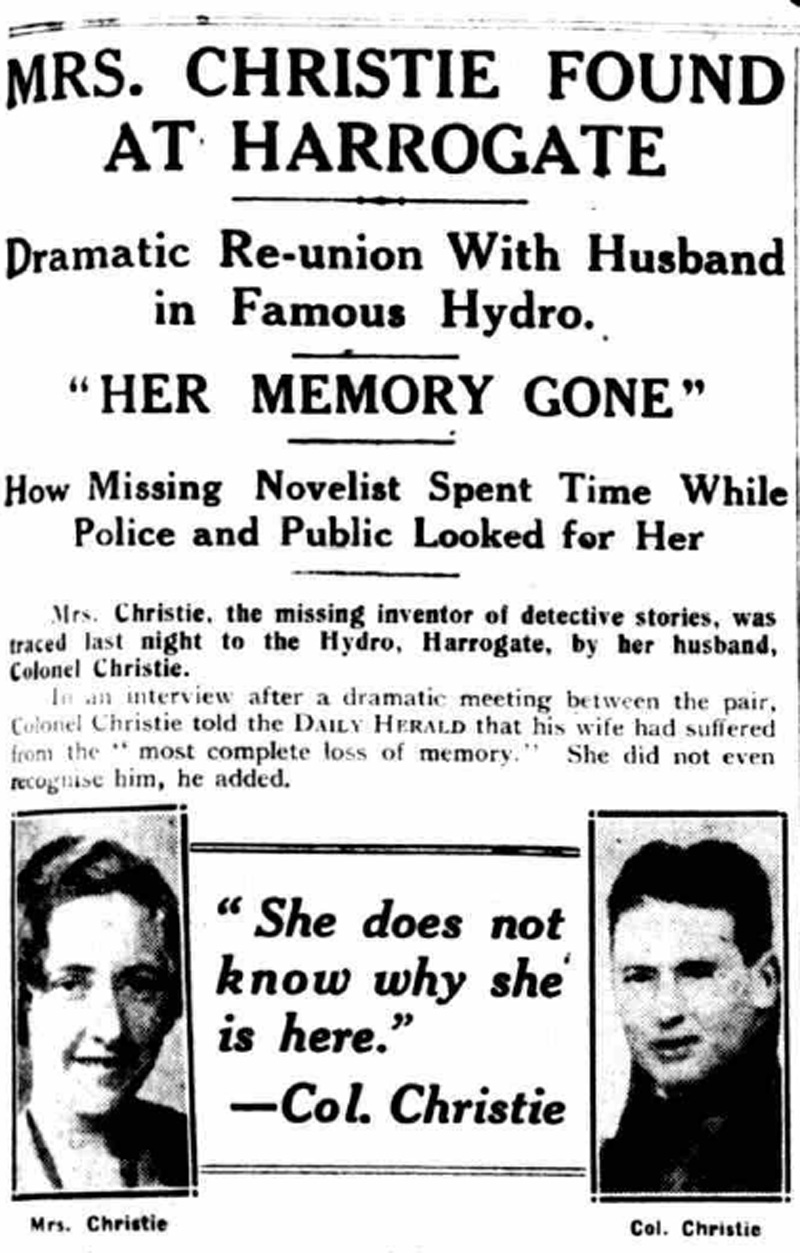

Eleven days later, Agatha was found in a spa hotel under an assumed name with no memory of how she got there. She might have suffered from a rare case of “fugue state,” out-of-body amnesia brought on by extreme stress.

But traumatic as the whole thing must have been, that incident and its repercussions set her on the greatest adventure of her life.

In her 40s, after breakdown and divorce, Agatha Christie found true love and became an archaeologist.

“I had a very happy childhood.”

In the year before her disappearance, Agatha Christie lost her beloved mother, Clarissa, while her husband Archie was working in Spain.

Archie returned after the funeral and suggested Agatha forget her duties and come away with him. Agatha found his cavalier attitude “very hard to bear when you have lost a person who is one of three you love best in the world.” She declined.

Archie left on holiday and, unknown to Agatha, started an affair with his former secretary. Agatha stayed behind to sort out her mother’s affairs at Ashfield, the family home.

The task proved too much to tackle alone. She fell into a deep depression, crying for no reason, forgetting how to sign a check. No doubt she went through clothing and photos, reminders of growing up in Torquay, a lovely English seaside town:

One of the luckiest things that can happen to you in life is to have a happy childhood. I had a very happy childhood.

When Agatha was eleven, her father died painfully of multiple heart attacks brought on by financial problems. He was a moneyed American who didn’t have a head for money.

Clarissa managed as best she could after his death. Agatha was home-schooled by her mother and left to roam the grounds of Ashfield.

“And then suddenly one morning, it had happened, England was at war.”

With the advent of World War I, Agatha became a nurse.

She started writing while working at a hospital dispensary, in the long wait between filling prescriptions. She also certified as an apothecary—knowledge she put to ingenious use later.

It wasn’t long before Agatha was swept off her feet by Archibald Christie, a Royal Flying Corps pilot, one of those “daring in young men in their flying machines.”

(Remember, the Wright brothers made their first flight only ten years before the onset of WWI.)

Archie immediately posted to France. War and hardship separated them.

At Christmas, while Archie was home on leave, they eloped to City Hall, then saw each other only two weeks during the next three years.

In 1918, after the war ended, Archie took an office job. In 1919, after a pregnancy that felt like a “nine-month ocean voyage to which you never get acclimatized,” Agatha had a baby girl, Rosalind.

And in 1920, she gave birth to Hercule Poiret in The Mysterious Affair at Styles.

It was a carefree time for the Christies. Agatha spun one book after another, each more popular than the last.

Archie did well in business. In 1922, he managed The Empire Exhibition, a tour to showcase “products of the British Empire” through Canada, New Zealand, South Africa, and Australia. Rosalind stayed with Agatha’s mother while her parents finally enjoyed a honeymoon.

Agatha Christie’s star continued to rise—until her mother’s death. She moved back to her childhood home for several months to manage her mother’s affairs.

Archie visited only once during that time—to ask for a divorce. He’d been having an affair with Nancy Neele, another member of The Empire Exhibition tour.

Undone by grief, betrayed by her husband, and on a tight publishing schedule, Agatha drove into the night and lost control, literally and figuratively.

The next morning, her abandoned car was found down a hillside near the manor where her husband Archie was staying with his mistress.

The media went mad. Her husband immediately became suspect. Arthur Conan Doyle, creator Sherlock Holmes, took one of Agatha’s gloves to a psychic to learn if she’d “passed over.”

Possibly suffering from amnesia and a concussion, she checked into Harrogate Spa Hotel. She didn’t recognize herself in the newspaper outcry that followed, but the one of the hotel band members did.

Somewhere between “Yes, We have No Bananas” and “Don’t Bring Lulu,” banjo player Bob Tappin noticed an elegantly-dressed woman in the ballroom who resembled Agatha. He informed the police, who called Archie. When Archie arrived, Agatha treated him like an acquaintance whom she couldn’t quite recall.

When her memory returned, she gave Archie his divorce.

“You certainly ought to go to Ur.”

In autumn 1928, after several months of therapy, Agatha decided to put her marriage behind her and seek out the sun. She considered Jamaica, but a chance dinner conversation inspired her to book passage on the Orient Express to Baghdad.

“You must go to Mosul—Basra you must visit,” her friend advised. “And you certainly ought to go to Ur.”

She’d been following tales of the famous archaeological site, Ur of Chaldees, in the newspapers. “I became wildly excited,” Agatha wrote later.

As it turned out, Katherine, wife of Ur’s director Leonard Woolley, was a fan. The two become great friends. (Agatha would later cast the beguiling but slightly crazed Katherine as the victim of Murder in Mesopotamia whom everyone had a motive to kill.)

Ur entranced Agatha:

The lure of the past came up to grab me. To see a dagger slowly appearing, with its gold glint, through the sand was romantic. The carefulness of lifting pots and objects from the soil filled me with a longing to be an archaeologist myself.

The Wooleys invited her back the following year.

When it came time to leave, they assigned Leonard’s 26-year-old assistant, Max Mallowan, as Agatha’s escort to Baghdad. She and Max got on famously despite their age difference. (Agatha was 40.)

When she received word her daughter Rosalind was ill, Max accompanied her back to England. (Rosalind fully recovered.) By the end of the year, they had married.

“The most perfect days I have ever known.”

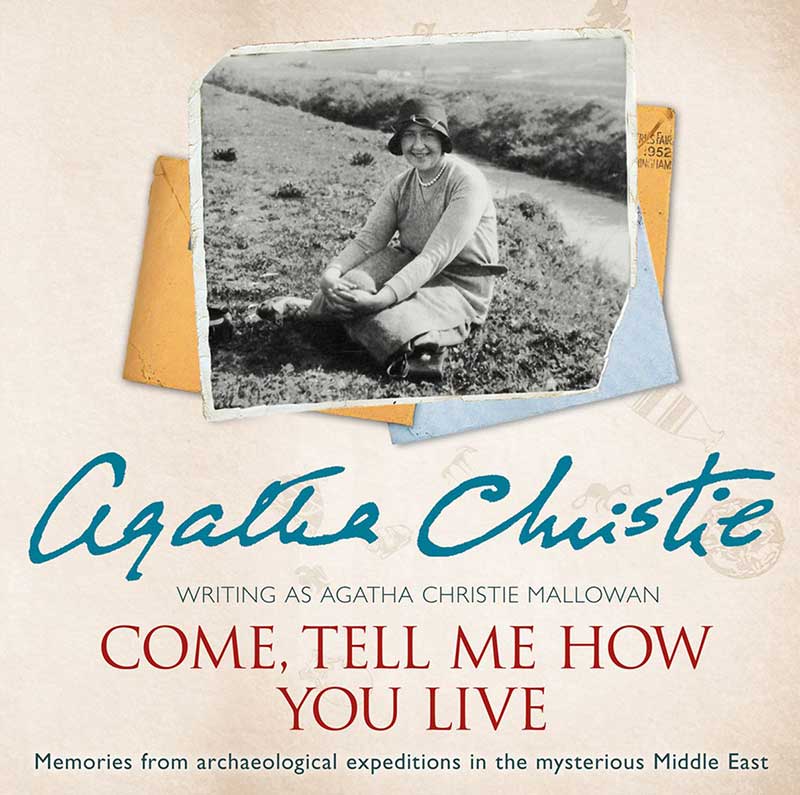

The Mallowans soon fell into their yearly rounds—autumn and spring digging in the Middle East, summers at Ashfield with Rosalind when school let out.

Agatha acted as the photographic technician on every dig, developing the prints herself, and discovered she a talent for pottery restoration.

She also found time to write, and some of her best books draw from her life in the Middle East—Murder on the Orient Express, Death on the Nile, Appointment with Death and of course, Murder in Mesopotamia (my favorite).

From 1949-1958, Max directed the spectacular site of Nimrud in Iraq, known for its ivories. Agatha pioneered the techniques used to preserve and clean them. Max noted:

For the preservation of the objects and their treatment in the field, Agatha’s controlled imagination came to our aid. She instantly realized that objects which had lived under water for over 2000 years had to be nursed back into a new and relatively arid climate…

Agatha painstakingly cleaned each ivory piece with an orange stick and diluted cold cream, a brilliant method.

She complained “…there was such a run on my face cream that there was nothing left for my poor old face after a couple of weeks!”

Despite being the bestselling novelist of all time and a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire, archaeology was the world Agatha Christie loved best.

She considered her days on site “some of the most perfect I have ever known.”

The Mallowans extraordinary union lasted 45 years, until Agatha’s death at age 85. In his memoirs, Max wrote: “Few men know what it is to live in harmony beside an imaginative, creative mind which inspires life with zest.”

Despite their age difference, he passed just two years later.

Why do I consider this unbelievably successful woman a Later Bloomer?

She tackled immense emotional pain with great courage. She could easily have hidden behind her “bestselling novelist” accolades.

At age 40, Agatha Christie faced her fears and took a chance. And that act led to a passion that transformed the rest of her life. (And if you enjoyed Agatha’s story, you’ll also find Freya Stark fascinating.)

Do you have a favorite Agatha Christie mystery?

Sources

- Christie, Agatha. An Autobiography. William Morrow Paperbacks; Reprint edition (September 11, 2012)

- Mallowan, Agatha Christie. Come, Tell Me How You Live. William Morrow Paperbacks; Reprint edition (April 10, 2012)

- Artwork: Babylon by František Kupka (1906).