Long ago on a trip to London, a friend and I stayed near Hyde Park in Kensington. We dragged our bags up six flights of stairs to the top floor (the cheapest room) and laughed at our luck.

Our tiny garret overlooked rows of Victorian rooftops, like a scene from Peter Pan. It’s easy to believe you can fly up there.

A century and or so earlier it would have been part of the nursery. The hotel once housed a wealthy Victorian family—a barrister named George Hunt, his wife, three sons, five daughters, their governess, and ten servants.

And the children would have shared that magical view with Beatrix Potter (1866-1943), who grew up a few streets away.

Many know Beatrix through her charming books or the 2006 movie Miss Potter. But the real Beatrix was complicated, fascinating, far ahead of her time, and a bona fide late bloomer.

She overcame an unhappy childhood and sexism to launch her famed writing career at age 36, married at 47, and embraced farming and conservation full-time in her 60s. She considered the latter activities her life’s calling and helped establish Great Britain’s National Trust.

Beatrix Potter’s Friends and Muses

But in an odd way, Beatrix resembled the Greek goddess Persephone. From November through June, those dark winters smothered in London fog (actually Industrial Revolution smog), she lived in her top floor nursery alone.

She was raised by servants and governesses and only saw her parents at dinner. Unlike the Hunt children, she had no human companions until a brother came along six years later.

But she wasn’t lonely. Her attic tribe included dogs and cats, rabbits and mice, and a bright green lizard named Judy. They were her friends and muses. She never tired of capturing their antics through stories and sketches. Her artistic talent developed early.

Beatrix’s parents both came from Manchester cotton-factory money and dabbled in the arts—Victorian “trustafarians.”

Beatrix’s mother, Helen, could embroider and paint, but she preferred the art of social-climbing via offspring. The shy, imaginative Beatrix would forever disappoint her. Beatrix’s father, Rupert, sat for the bar but never practiced. He took up photography and in 1869, he was elected to the Photographic Society of London.

Beatrix wanted for nothing but her parents’ love and attention. And like Persephone, she came alive each summer.

From July through October, the family fled London’s sweltering streets for the countryside. For Beatrix’s first fifteen years, they lived at Dalguise House on the River Tay in Scotland.

There, while her father took pictures and her mother made connections, Beatrix ran wild with her pets, collected butterflies, identified birds, and listened to “the music sweetest mortal ears can hear, the murmuring of the wind through the fir trees.”

Her Scottish governess, Ann MacKenzie, filled her young head with stories of witches and fairy folk, magic and talking animals. Beatrix recalled,

I used to half believe and wholly play with fairies when I was a child. What heaven can be more real than to retain the spirit world of childhood, tempered and balanced by knowledge and common-sense.

When Beatrix was sixteen, her father announced that Dalguise House was no longer available. At first, she was devastated. “The memory of that home is the only bit of childhood I have left.” But within a few weeks, Rupert leased Wray Castle, a romantic pile on the western shore of Windermere in the Lake District.

Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley, the local vicar, welcomed them to the community. He would become one of the three founders of the National Trust and a major influence on Beatrix. The beauty of her new summer home soon enveloped her soul.

Her self-absorbed parents at least recognized her talent, and at age 15, Beatrix received an Art Student’s certification, her only formal schooling. A succession of governesses taught her to read, write, and speak French and German. She once wrote to a friend,

Thank goodness, my education was neglected. I was never sent to school…it would have rubbed off some of the originality.

Fungi and Sexism

With her love of nature and gift for art, Beatrix Potter soon became enamored with natural history. It was an acceptable hobby for Victorian women, especially if they concerned themselves with flowers, birds, and butterflies.

Beatrix, however, developed a passion for mushrooms.

She lived near the Natural History Museum and spent hours there studying prints and specimens. She taught herself to draw live sections under a microscope.

Charles MacIntosh, a childhood friend from Dalguise (and model for Peter Rabbit’s nemesis Mr. McGregor), also encouraged her. As the district’s postman/naturalist, he roamed miles every day through the country. He knew fungi by sight and by Latin name and mailed labeled specimens to Beatrix in London.

“His judgement,” Beatrix observed, “…gave me infinitely more pleasure than that of critics who assume more, and know less than poor Charlie. He is the perfect dragon of erudition, and no gardener’s Latin either.”

By age 28, Beatrix Potter had documented seventy-three types of fungi in full color, including sectional views.

Three years later, she wrote a paper titled “On the Germination of the Spores of Agaricineae.” Her uncle, famed chemist Sir Henry Roscoe, helped her get it before the Linnean Society, the world’s oldest biology peer-review group. (As a woman, Beatrix was not allowed to present the paper, or even attend.)

The Society returned the paper with feedback, though we don’t know what kind. Beatrix withdrew it and never resubmitted it.

Today, Beatrix Potter’s work as a mycologist is widely recognized. In 1967, William Findlay, president of the British Mycology Society, used her paintings to illustrate his field guide to Britain’s fungi and lichens. She was the first person in Britain to document the rare parasitic fungus Tremella simplex, recently rediscovered in Aberdeen.

And in 1997, the Linnean Society issued her a posthumous apology. Why did she walk away from that world?

The sexism (what she sarcastically called the “grown-up world”) of science frustrated her. But biographer Linda Lear believes that Beatrix desperately needed a way to both use her gifts and gain independence from her parents. “She had explored scientific illustration and research and found that, however intriguing, it could not satisfy that end.”

But she’d conceived another idea that might.

Fame and Heartbreak

It started as a series of illustrated letters written to the oft-sickly son of a former governess, Annie Moore. Seven years later, Beatrix asked to borrow the letters back and turned them into The Tale of Peter Rabbit.

Six publishers rejected the book, so Beatrix published her own edition. After two successful printings, her Lake District mentor Canon Rawnsley determined to see her traditionally published.

He sent Peter Rabbit to Frederick Warne & Co. They took a chance on “the bunny book” (as one partner scornfully called it) and signed a contract with Beatrix in June 1902. The printing sold out immediately.

At age 36, Beatrix Potter, an eccentric Victorian spinster whose closest friends still included rats, mice, rabbits, and hedgehogs, was set to become one of the world’s most celebrated children’s authors.

Beatrix’s editor was Norman Warne, youngest of the three brothers who ran the company. Their professional relationship soon bloomed into love. On July 25, 1905, a few days before her 39th birthday, Norman asked Beatrix to marry him, and she accepted.

Helen and Rupert kicked up a fuss and refused their blessing. Helen, in particular, loathed the idea of her daughter marrying into “trade.” Beatrix saw the irony of that. “Publishing books,” she wrote to a cousin, “is as clean a trade as spinning cotton,”—the profession of her mother’s parents.

Her parents insisted she join them on the annual Lake District holiday (hoping it would cool her ardor) and she complied.

A month to the day after her engagement, Beatrice received a devastating letter from Norman’s sister. Norman had died suddenly from pernicious anemia (a form of treatable leukemia today).

Beatrix retreated to Near Sawrey, a tiny Lake District village she’d come to love nine summers earlier. She and Norman wanted to start married life there, far from her meddling parents. Beatrix purchased a farm called Hill Top to honor their dream. It would be many years before she could truly settle there.

In her grief, she pushed herself creatively, writing and illustrating thirteen stories over the next eight years. She also lived a double life.

Most of the year, Beatrix played the dutiful London spinster who cared for her aging parents. But during the summer, Beatrix returned to Hill Top Farm and became a Lake District countrywoman—albeit a wealthy and successful one.

Beatrix’s entrepreneurial vision saw all the ways she could bring her characters to life. She created one of the first merchandising lines around Peter Rabbit and his friends—dolls, slippers, handkerchiefs, wooden puzzles, nursery wallpaper, a board game, and more.

Decades later, Walt Disney would contact Beatrix Potter to acquire The Tale of Peter Rabbit. She didn’t feel Disney would stay true to her franchise. He went away disappointed.

Fells and Love

When Beatrix bought Hill Top Farm, her father’s firm acted on her behalf. Later she found that she’d been thoroughly fleeced (no pun intended). So in 1908, she hired W. H. Heelis & Son, local Lake District solicitors, to represent future dealings.

Over the next five years, with the help of William Heelis, Beatrix bought fourteen more farms. As with Norman Warne, respect and friendship blossomed into love. In late 1912, William asked her to marry him.

Her parents again threw a fit. They expected her to care for them in their old age, and Beatrix still managed their large London household. Beatrix stood her ground.

The following August, at age 47, she became Mrs. Heelis, the only name she went by in the Lake District. Her loving partnership with William would last 33 years.

Beatrix’s father Rupert passed a few years later, and Beatrix convinced Helen to buy an extravagant Lake District property. At age 50, Beatrix finally became a full-time resident of the place she loved best on earth.

As her eyesight dimmed, Beatrix wrote less and spent more time farming and sheep breeding. She and William bought several more properties, including a farm that once belonged to her cotton-spinning great-grandfather.

They didn’t acquire for profit, but to conserve the Lake District’s farming methods and landscape (especially the “fells” or high ground used for common grazing). They’d always planned to leave their holdings to Canon Rawnsley’s charitable venture, The National Trust.

At age 77, Beatrix Potter passed away from pneumonia. William followed her eighteen months later. At his death, fifteen farms, several houses and cottages, and 4300 acres came under the Trust’s protection.

The majority of the Lake District remains undeveloped to this day because of Beatrix and William’s bequest.

Beatrix Potter found her first career choice closed to her and lost her first love to illness. Yet she persevered and followed art, nature, and writing lead her to new passions and places. She proves that late-blooming often brings surprising and wonderful results.

If you enjoyed this story, you’ll love reading about Mary Granville Delany, who created the art of mixed media collage at age 72.

More About Beatrix

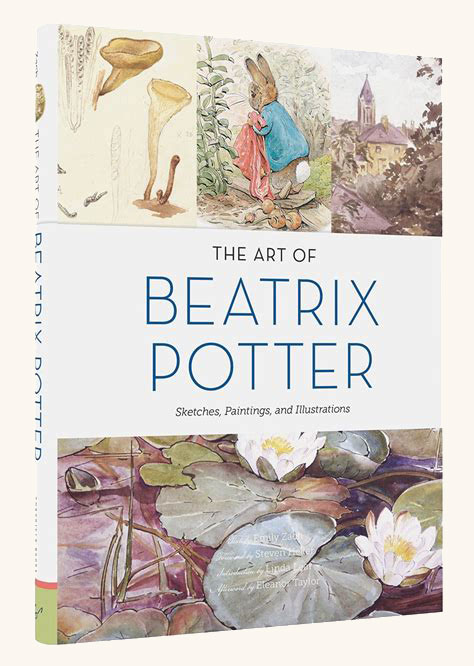

- The opening image of Hunca Munca and her baby is from The Tale of Two Bad Mice. Beatrix reproduced this scene in porcelain as part of her merchandising line. Almost all her fictional characters had real-life counterparts among her pets.

- Beatrix’s works came into the public domain in 2014, seventy years after her death. One of my favorite authors, Frank Delaney, wrote a piece about her for The Public Domain Review.