Caroline Herschel (1750-1848) was the first woman to discover a comet and receive the Royal Astronomical Society’s Gold Medal.

Yet she experienced such childhood cruelty, she called herself as Cinderella. She overcame abuse, neglect, and disfigurement to find her place among the stars at age 36.

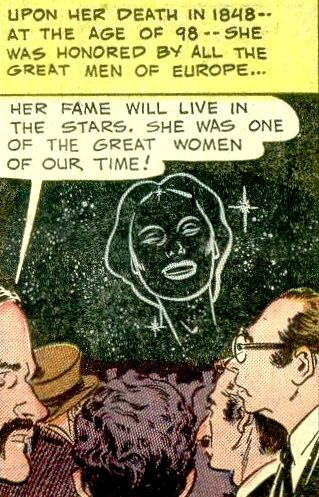

And although you might not recognize her name, DC Comics immortalized it in a famous graphic novel.

A Childhood of Cinders

Caroline was born in Hanover, Germany on March 16, 1750, the fifth child of Isaac Herschel and Anna Ilse Moritzen. Isaac encouraged all of his children, including his elder daughter, to learn French, music, and mathematics.

But Caroline contracted smallpox at age three, which disfigured one eye. At age 10, she came down with typhus and stopped growing. She remained just over four-feet tall for the rest of her life. Her mother decided that her daughter’s only value was as the family’s slave. Caroline later wrote:

But as it was my lot to be the Cinderella of the family…I could never find time for improving myself…except what little I knew of music…which my father took a pleasure in teaching me. N.B. When my mother was not at home. Amen.

The Seven Years’ War eventually forced most of Caroline’s brothers to leave Germany and caused Isaac’s death. Caroline was left alone with her mother and eldest brother, Jacob, both of whom beat her: “And poor I got many a whipping for being slow at the task of footman or waiter.”

Her favorite brother William, twelve years her senior, contrived to rescue his beloved “Lina” when she was 22.

William had moved to England several years earlier. He became a sought-after music teacher and organist. On a visit to Hanover, William miraculously convinced Anna Ilse to let Caroline return with him to Bath temporarily—supposedly because he needed a soprano for his oratorios.

William gave Caroline daily voice lessons. She quickly mastered English and became an admired soloist wherever he played.

William also trained her to assist with his favorite hobby—astronomy.

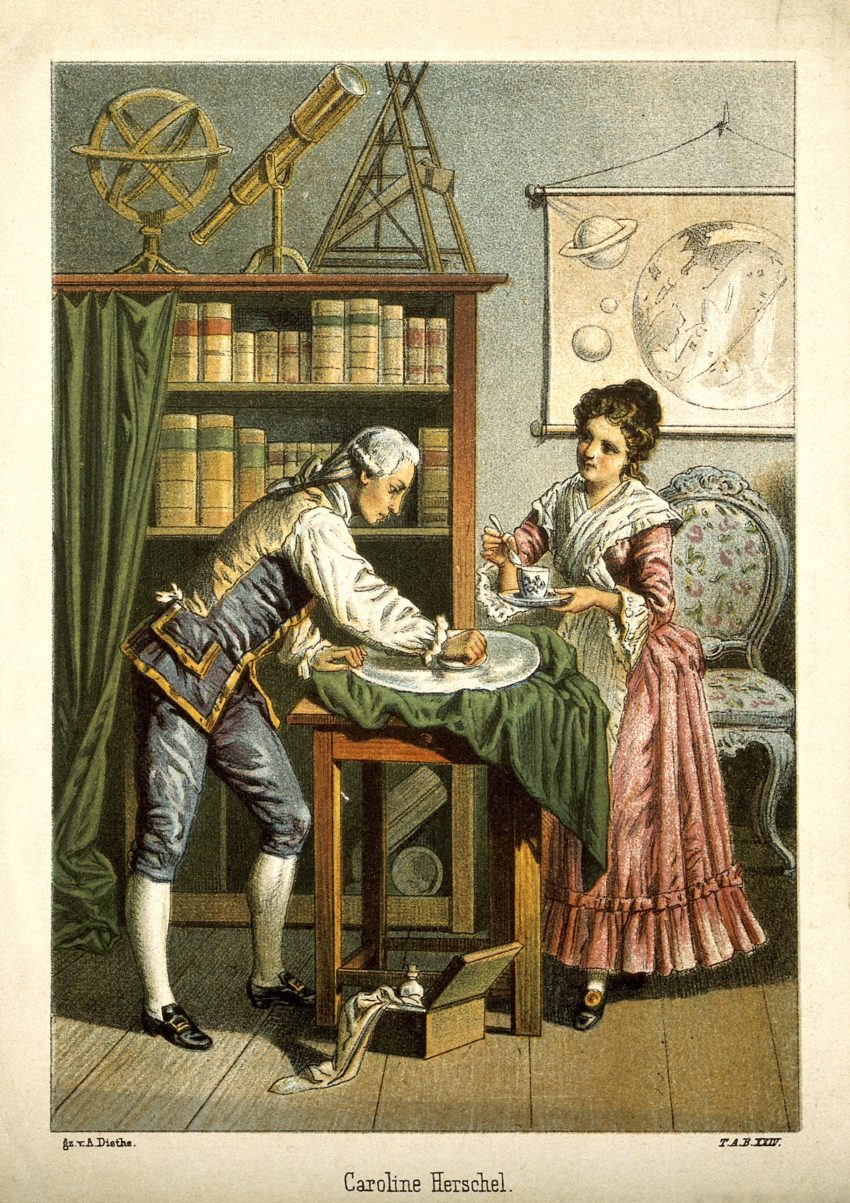

At first, she polished the mirrors used to collect light (as William is doing in the image above). Then she learned to make calculations from William’s observations, even though she knew no multiplication. (She worked from a cheat sheet.) Finally, William gave her a small telescope of her own.

For Caroline, there was no going back.

A Life Among the Stars

One night in 1781, William observed what he thought was a comet through his homemade telescope. He’d actually discovered the planet Uranus, which he named Georgium Sidus (the Georgian planet), after King George III.

SkyandTelescope.com notes that:

Locating this ice giant was the most revolutionary discovery since Galileo spotted the moons of Jupiter 170 years earlier. Herschel became an instant celebrity and won a stipend from the King of England that allowed him to become a full-time astronomer.

The catch—William must relocate to Windsor and entertain royal dinner guests with star-gazing shows. Caroline hated Windsor at first. She missed musical Bath and resented the backwater life of a country research assistant.

But William built her a special telescope and before long she noted 41 objects (mainly nebulae) from the famous catalog of astronomer Charles Messier.

In 1783, while observing Messier 31, the Andromeda Galaxy, she discovered the galaxy now designated NGC 253 (sometimes called the Silver Dollar Galaxy).

But for the next three years, she had little time for her own discoveries.

William needed her as his scribe, since moving from telescope to candlelight meant that “…the eye could never return soon enough to that full dilatation of the iris which is absolutely required for delicate observations.”

He yelled his findings to Caroline, who sat in a makeshift hut to block the light from her candle. She looked forward to his trips abroad.

The employment of writing down the observations, when my Brother uses the 20-feet reflector, does not often allow me time to look at the heavens; but as he is now on a visit to Germany, I have taken the opportunity of his absence, to sweep in the neighbourhood of the sun, in search of comets….

On August 1, 1786, Caroline saw a hazy object moving through the constellation Leo. Before going to sleep she dispatched a letter to Dr. Charles Blagden, Secretary of the Royal Society, announcing her find.

Five days later, Dr. Blagden and his deputation knocked on Caroline’s door.

They confirmed she’d discovered a comet, becoming history’s first woman to do so. At age 36, she began her life’s work.

When William returned from Germany on August 16, King George immediately summoned him to Windsor to show off the “first lady’s comet.”

Caroline herself seldom visited court, but George gave her £50 a year to assist William, making her the first professional woman astronomer. Caroline went on to discover seven more comets and become a celebrity.

Immortalized in Popular Culture

William died when Caroline was 72, but she continued to verify and confirm his findings.

When she was 78, the Royal Astronomical Society awarded her a Gold Medal for her catalog of 1500 nebulae. No woman would repeat that honor until Vera Rubin in 1996.

At age 86, she and late bloomer Mary Somerville became the first two female members of the Society. And at age 96, Caroline received the Gold Medal for Science from the King of Prussia.

Before she died two years later, at age 98, she penned her own epitaph. It reads:

The eyes of her who is glorified here below turned to the starry heavens.

All eight comets Caroline discovered bear her name, as does the Moon’s crater C. Herschel.

Although 36 may seem young to be classified as a “late” bloomer, she overcame so much to find that sanctuary under the stars.

In 1952, DC Comics immortalized Caroline in Wonder Woman #51, another singular tribute to the tiny, determined woman whose vast passion changed how we view the cosmos.

Opening Image: NGC-7380 otherwise known was The Wizard Nebula