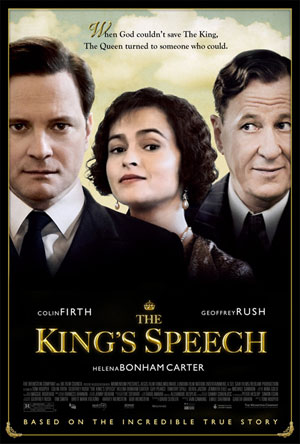

The morning after the 2011 Oscars, my inbox flooded with messages. Did you watch the Academy Awards? Did you hear David Seidler’s Best Original Screenplay acceptance speech?

I knew Seidler had been nominated for The King’s Speech, but why the fuss?

Hubby and I had left town for the weekend because it was our anniversary and we had no desire to celebrate Oscar traffic madness.

We live two miles from the Kodak Theatre and found signs in our neighborhood telling the limousines where to go (using much politer than I’ve been known to use)!

So I missed Seidler’s quip, “My father always said to me I’d be a late bloomer.” Once back in town, I looked him up. Initially, I thought Seidler a late achiever, not a late bloomer. He’s been writing all his life.

But I soon discovered his heartrending reason for becoming a writer—he felt it was his only way to be heard. Seidler had been a stutterer like George VI, the subject of his screenplay. Writing was a tool. Telling the King’s story was his life-long passion.

Surviving The Blitz

David Seidler (b. 1937) was a toddler during the 76 nights of terror known as the London Blitz. His father moved the family to Surrey, “which was probably a good idea since an incendiary bomb fell through the ceiling of my nursery [in London] a couple of weeks later,” Seidler recounts.

He next remembers:

We were on a ship in a convoy of three ships, and had a fighter escort for a few days, but then it got out of range. There was a lot of hubbub and fear about U-boats. The men were put on submarine watch. It was very tense.

The Germans hit and sunk one of the ships, killing everyone on board. By the time Seidler and his family reached New York, he was terrified and had developed a stutter.

One thing gave him hope he could recover — the radio speeches of George VI, who was a stutterer himself. Young David’s parents encouraged him by saying, Listen to the King now. He’s not perfect. But he can give magnificent, stirring speeches.

Young David knew his stammer made people uncomfortable, so he kept his mouth shut. He resolved to become a writer in order to be heard.

But at 16, his shyness gave way to anger for all he’d missed—going on dates, speaking in class, living a normal life. In a rage, he dropped a perfectly-enunciated F-bomb. Within two weeks, his stammer was gone.

Making Up For Lost Time

Wikipedia gives the impression that Seidler graduated from Cornell at 22 and mysteriously arrived in Hollywood to work for Coppola at age 40. Filling in those lost years took some detective work.

Although Seidler first considered writing George VI’s story in college, he got sidetracked by his studies and by girls (he had to make up for lost time, after all). After graduation, he wrote dubbing dialog for the Godzilla movies and scripted an Australian TV series, The Adventures of the Seaspray, about a widowed journalist who lives on a schooner with his three children.

On a New Zealand trout-fishing trip in his early 30s, Seidler fell in love with Huia, a Maori woman. They married and had a son, Marc. Through a series of strange connections, Seidler became chief propaganda writer for Fijian independence leader Ratu Kamisese Mara. He quit three years later when the job became too dangerous:

My car was forced off the road a few times and I got knocked out. I had a wife and young child and knew they were vulnerable so it was time to leave.

Although he and Huia eventually separated, he moved to New Zealand to be near Marc. (They’re still close. Every year they take a month-long wilderness trip together.) While there, he became a creative director for McCann-Erickson.

Yet George VI’s story never left him. His chance for Hollywood came as he neared 40. His old classmate, Francis Ford Coppola, tapped him to write the script for Tucker: A Man And His Dream. But the project ended up in development hell.

I was under the naive impression that Tucker would change my life and that I could do everything in Hollywood, and of course I realized it wasn’t true.

Tucker took ten years to get made, only to bomb at the box office.

Beating The Odds

Seidler finally returned to the story of George VI, born Albert Frederick Arthur George—”Bertie” to those close to him, which was how Seidler now felt. His research turned up Bertie’s speech therapist, Lionel Logue.

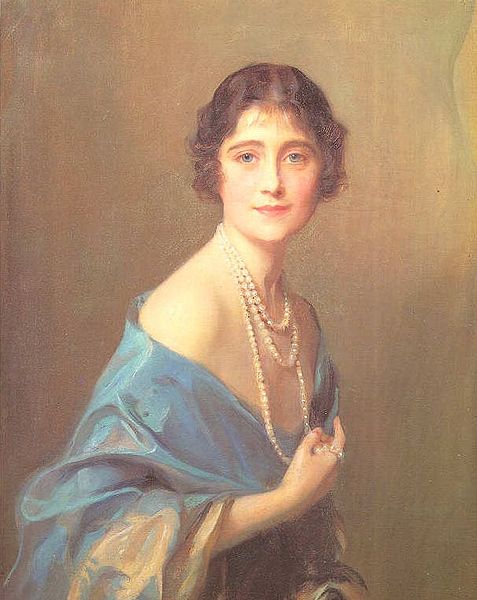

Seidler tracked down Logue’s son, Valentine, a retired brain surgeon, who promised access to his father’s notebooks on one condition—Seidler must get written permission from the Queen Mum.

So I wrote to the Queen Mum, and she wrote back, “Please, not in my lifetime. The memory of those events is still too painful.” And when the Queen Mum says to an Englishman, “Wait,” an Englishman waits. I didn’t figure I’d have to wait this long.

Queen Mum held on for another 25 years, to the ripe old age of 101.

In the meantime, Seidler remarried. With two youngsters to support, he became something of a Hollywood hack, writing TV movies such as Come On, Get Happy: The Partridge Family Story. “In retrospect, I made not brilliant career choices,” he says. “I did what I had to do.”

The Queen Mum passed away in 2002, but Seidler was bogged down with other projects.

Then, late in 2005, Seidler was diagnosed with bladder cancer. He thought, “Well, David, if you’re not going to tell Bertie’s story now, when exactly do you intend to tell it?”

Turns out, Bertie himself was a late bloomer. He wasn’t meant to be king. But his older brother, Edward VIII, abdicated to marry American divorcee and Nazi sympathizer, Wallis Simpson. (Seidler considers it the most selfish love story ever told.)

At age 41, with England on the brink of war, the stuttering Bertie transformed himself into George VI. The Queen Mum believed the stress contributed to his death at the young age of 56. His people remember him as The Good King.

I did my best to do justice to a largely forgotten story about a king who, aided by a remarkable therapist, overcame a speech impediment to lead his country through some of its darkest hours.

And using non-traditional therapy, Seidler overcame his darkest hour—he beat his cancer and finished the script.

For purposes of this blog, I define Later Bloomers as people who don’t realize their creative passion until later, or who discover it early but can’t pursue it until adulthood.

David Seidler’s stutter pointed him toward writing, but his passion was giving voice to a king, and in the process, inspiring others who live in silence. It may have taken him 50 years, but it was worth the wait!

If you look closely you’ll see the real unifying thread [of many of his projects] is that they’re stories about people who’ve had the courage to change their seemingly preordained destinies. That’s what interests me.

Sources

Sources

- CNN (on beating cancer)

- Seidler’s Academy Award Acceptance Speech