“True originality consists not in a new manner but in a new vision.” ~Edith Wharton

I count Downton Abbey my one marital costume drama triumph.

I’m not sure how I convinced my English husband to watch the first episode, but I thank Julian Fellowes’ superb writing for keeping him riveted. We had one memorable weekend of silk and corsets together.

In Downton Abbey, Elizabeth McGovern plays Cora Crawley, Lady Grantham, an American heiress who saves the ancestral home from bankruptcy. In reality, over a hundred American heiresses married into the English peerage during that era. They became veritable historical preservation league.

Late-blooming writer Edith Wharton (1862-1937) knew many of those real-life Cora Crawleys. If she’d been richer or prettier, she might have been one.

The Fairy Child

Edith Newbold Jones was born on January 24, 1862 in New York City. Some say her great-aunts were the Joneses, as in “keeping up with the Joneses.”

Although her peers produced the real Cora Crawleys, Edith’s family went abroad in 1866 to live on the cheap. A string of European governesses taught her French, Italian, and German. She taught herself to read and began a life-long affair with books, the only love that remained faithful to her.

Edith’s writing aspirations surfaced early. She published a short story at age 15, but her parents belittled her efforts. In an unfinished autobiography, she wrote that they regarded her with fear, “like some pale predestined child who disappears at night to dance with ‘the little people’.”

They needed her to marry up the social ladder, or at least not plummet from it.

Edward “Teddy” Wharton was 12 years her senior, a friend of her brother. He had a magnificent trust fund. They wed when Edith was practically a spinster of 23 and lived the high life for a while—yearly trips abroad, a Georgian manse even Lady Grantham would envy.

But as in Downton Abbey, it’s no cliché: “Money doesn’t buy happiness.”

“Life is always a tightrope or a feather bed. Give me the tightrope.” ~Edith Wharton

Teddy was an alcoholic obsessed with barely-legal girls. Modern biographers think he also suffered from bipolar disorder. Divorce was out of the question. For the first twelve years of her marriage, Edith suffered debilitating ill-health.

Then something happened that none of her biographers adequately explain. At age 35, twenty years after her first publication, Edith started writing again. That book, The Decoration of Houses, covered home decor for the genteel and prosperous, exhorting them to rethink their claustrophobic drawing rooms and abolish the “wobbly velvet-covered tables littered in geegaws.”

She published at least a book a year after that—travelogues, home decor, short story collections, plus two of her best-known novels, The House of Mirth (1905) and Ethan Frome (1911). The advances and royalties made her rich in her own right.

In 1907, Edith discovered Teddy siphoning off her money to support his mistress. She left him and moved to Paris. In 1913, she divorced him. Finally, in her 50s, she could write without the insanity.

But World War I intervened. Edith became a passionate supporter of the Allies. She raised funds and helped create hostels for French and Belgian refugees. In 1916, she received a French Legion of Honour knighthood for her volunteer work.

In 1920, at age 59, Edith published The Age of Innocence, a deft and devastating account of the machinations conducted in the heavy drawing rooms of her decor books.

She won the Pulitzer for it—the first woman to do so.

An Awkward Creature

Not surprisingly, Edith’s novels describe people trapped by their circumstances, unable to break free of suffocating social conventions.

English novelist Anita Brookner, writing in The Telegraph, basically calls her the anti-Austen. Readers “habituated to the formula established by Jane Austen, with a tightly constructed happy ending” will find her difficult, even disturbing. Brookner concludes:

Born to great wealth, owner of beautiful houses, she was in essence that awkward creature, a born writer.

And once she started writing she never stopped. She died of a stroke at age 75, the pages of her unfinished book, The Buccaneers, scattered upon the floor. She experienced forty years of creativity, despite parental disapproval, a bad marriage, and war.

If you’re unfamiliar with Edith’s work, start with any one of these stunningly-adapted costume dramas (and don’t forget to invite your significant other): The Age of Innocence with Daniel Day-Lewis (directed by Scorsese), The House of Mirth with Gillian Anderson (X-Files’ Scully proving her acting mettle), Ethan Frome with Liam Neeson, or The Buccaneers (finished by another writer after Edith’s death) with Mira Sorvino. Edith based The Buccaneers on her circle of friends.

Do you have a favorite Edith Wharton novel?

Sources

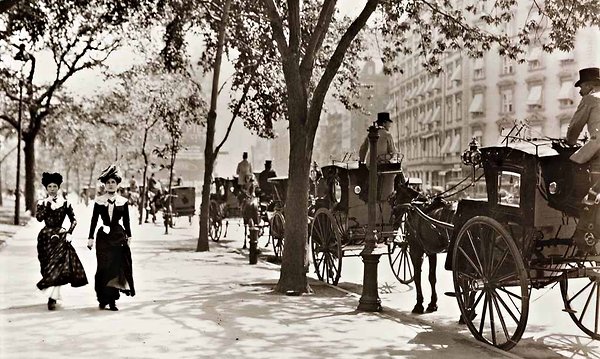

- Artwork at beginning: Central Park by Maurice Prendergast (1901) depicts Edith’s era.

- New York Times, January 19, 2012: For Edith Wharton’s Birthday, Hail Ultimate Social Climbers.

- New York Times Slideshow: Edith Wharton Turns 150.

- The New Yorker: The Changeling by John Updike.