Success is outliving your failures. ~Erma Bombeck

Erma Bombeck (1927-1996) possessed something that makes any woman a stunner. It wasn’t fake-white teeth, air-brushed skin, or surgically-enhanced, well, everything.

Erma had humor. Not the veiled cruelty that often passes for humor today. The real thing, in all its poignancy and compassion.

She inspired laugh lines in a generation that never anticipated botox.

Erma Bombeck would have turned 93 on February 21st. We’re all born dying, but Erma knew by age 20 what would kill her.

That’s when she discovered she had life-threatening kidney disease, probably inherited from her father, who died when she was nine. Perhaps her illness let her see life differently.

Whatever the reason, Erma Bombeck became America’s most beloved humorist. And she was almost forty when she penned her first syndicated column.

Erma Bombeck, Child Genius

Erma was both a young genius and a late bloomer. She grew up in Dayton, Ohio, and wrote for her junior high school newspaper. She became confident in her calling. At age 15, she marched into The Dayton Herald and demanded a job:

“I want to work for your paper.” The editor explained that only a full-time position was available.

“That’s okay, I can work two weeks and get you another girl to work the two weeks I’m in school. While she’s in school, I’ll work. That’s how our school operates. It’ll be just like having a full-time person.”

The Herald hired Erma as a “copygirl.” At age 16, she got her big break interviewing Shirley Temple (who was also 16). That earned her the staff award for feature of the week—$10 and a spot on the bulletin board. She thought her career was made.

At 17, Erma left home to study at Ohio University, 137 miles away. But despite her phenomenal journalism background, the college newspaper rejected her submissions. She barely passed freshman composition. Suddenly, she was the small fish in a big pond.

Erma began to doubt her calling. “If I can’t write, what am I going to do with my life?” Not long after, she discovered she had kidney disease, probably inherited from her father, who died when she was nine. She was still in her teens and it already felt like her life was over.

Erma came home and enrolled at the University of Dayton, a small Catholic college. During her sophomore year, she found a mentor in Brother Tom Price, who’d read some of her earlier pieces. He asked her to write for the university’s magazine.

One day, after reviewing her submission, he uttered three words that kept her going for the rest of her life.

“You can write,” he said. “You can write.“

The support of Brother Price and The University of Dayton transformed Erma’s life. She graduated in 1949 and married Bill Bombeck, a fellow student. It had been “love at first sight,” but they waited until he finished college after serving in World War II. Not surprisingly, she also converted to Catholicism.

After graduation, Erma wrote a “lady’s column” for the local newspaper, but aspired to the more exciting “city side” dominated by the men.

As her biographer, Lynn Hutner Colwell explains,

Women’s departments were a bit of a joke and no one was more aware of it than the women themselves. While there were a few women on the city side, for the most part, female reporters’ stories rarely made the front page.

Erma and Bill also wanted children, but doctors confirmed Erma couldn’t conceive. In 1953, the couple adopted a daughter, Betsy. Erma quit working to stay home with her.

Of course, she became pregnant within six months. Son Andrew was born in 1955, and son Matthew was born three years later. In 1959, Bill got a teaching job in Centerville, Ohio, so the family moved. Phil Donahue, his wife, and five children lived across the street.

They were happy years, but nothing prepared Erma for motherhood.

Erma Bombeck, ’50s Housewife and Late Bloomer

In the 1950s, women didn’t discuss the downside of caring for three children under school age—the exhaustion, the loneliness, the constant diaper changing and washing. Erma thought something was wrong with her.

To bury her feelings, she embraced the cult of domesticity, crocheted doorknob covers, carved zucchini roses for Bill’s dinner plate. It didn’t help. Later, seen through the balm of time and humor, she would write about those days in I Lost Everything in the Post-Natal Depression.

As she neared 40 and her youngest started first grade, she was ready to bloom:

That’s when I used to sit at the kitchen window, year after year, watching women like Ruth Gordon, Anne Morrow Lindbergh and Golda Meir carving out their own careers. I decided that it wasn’t fulfilling to clean chrome faucets with a toothbrush.

In an echo of that confident younger-self, Erma walked into the local newspaper office and offered to write a weekly column. She pitched what was basically Real Housewives of the 1950s without the backstabbing. The editor offered her three dollars a week. They shook on it.

It was a hit. A year later, Glenn Thompson, editor of the Dayton Journal-Herald, hired her to write a humor column for $50 a week. He also got it syndicated.

The column ran for more than thirty years. At the height of her popularity, 900 newspapers syndicated her writing to over 30 million people.

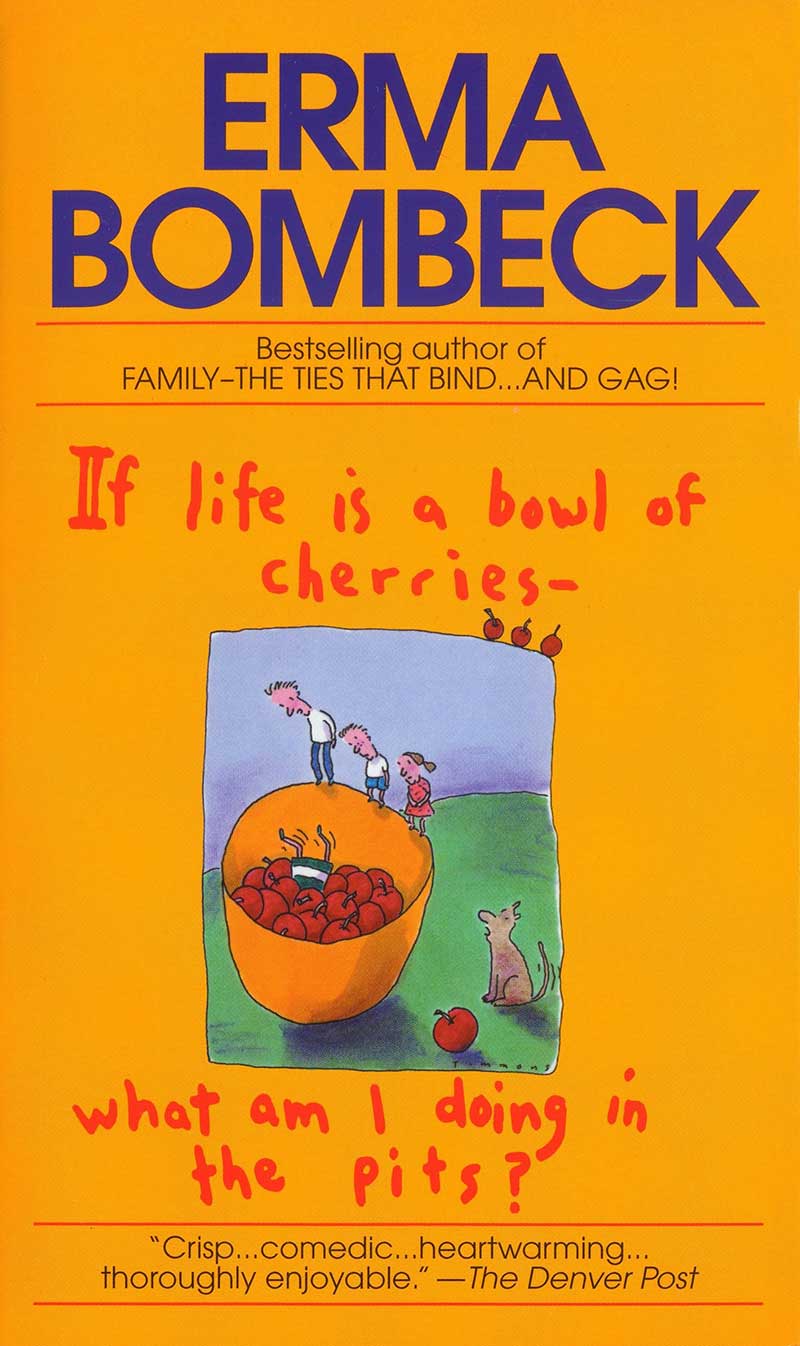

Erma went on to publish fifteen books, most of which became bestsellers. The titles say it all—Just Wait Till You Have Children of Your Own! (1971), The Grass Is Always Greener Over The Septic Tank (1976), and Motherhood: The Second Oldest Profession (1983)—to name just three.

Hollywood Calls

From 1975 to 1986, Erma joined the cast of Good Morning America. She became known for her hysterical quips and celebrity interviews, which included talking to Zsa Zsa Gabor on the actress’s king-size bed.

But not everything Erma touched turned to gold. In the late 1970s and early ’80s, Erma wrote a TV movie starring Carole Burnett that bombed and a sitcom that the network canceled after eight weeks.

And her kids didn’t always think much of her profession. Once, when asked what his mother did, young Matt answered that she was a “professional communist.”

After her Hollywood career fizzled, Erma focused on her strong suit—writing. In 1988, she signed a contract with Harper & Row valued by publishing experts at $12 million.

Erma Bombeck’s Legacy

In 1992, at age 65, Erma learned she had breast cancer. She underwent a mastectomy and seemed to have beat it. But within a year, her kidneys started to fail, and she needed dialysis. Erma Bombeck died far too soon from complications after a kidney transplant at age 69.

In 2000, Erma’s alma mater founded the Erma Bombeck Writers’ Workshop in her honor. The workshop runs every other year. It’s the only one in the country devoted to both humor and human interest writing.

The next one takes place from April 2-4, 2020, but it sold out within hours. There is a waiting list.

The University of Dayton also offers a Humorist-in-Residence Contest. If selected, you receive a spot in the workshop and two weeks at a hotel in Dayton to write.

These are fantastic opportunities for late-blooming humor writers to launch!

If you’re looking for more inspiration, you might also enjoy reading about these popular late-blooming authors:

- Lilian Jackson Braun: An Unsung Late Bloomer and Her Genius Cat

- Why 26 Publishers Rejected Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle In Time

Let the Wrinkles Roll

Shakespeare said, “With mirth and laughter let old wrinkles come.” When next you contemplate the media’s idea of beauty, remember Erma Bombeck’s late-blooming wisdom:

- “I am not a glutton—I am an explorer of food.”

- “Sometimes I can’t figure designers out. It’s as if they flunked human anatomy.”

- “The only reason I would take up jogging is so that I could hear heavy breathing again.”

- “What we’re really talking about is a wonderful day set aside on the fourth Thursday of November when no one diets. I mean, why else would they call it Thanksgiving?”

Do you have a favorite Erma-ism?

Sources

- Erma Bombeck: A Life in Humor by Susan Edwards

- Erma Bombeck: Writer and Humorist by Lynn Hutner Colwell

- The Erma Bombeck Collection at the University of Dayton

- Erma’s New York Times 1996 Obituary

Opening Image: Goutweed-grass, Pargolovo by Ivan Shiskin (1885) in honor of Erma’s book, The Grass is Always Greener Over the Sceptic Tank.