She was born the heiress to a vast fortune. But in her 40s, she developed a late-blooming compulsion for crime.

Not committing it, solving it.

Many experts consider Frances Glessner Lee (1878-1962), a no-nonsense granny born in the Victorian era, “the godmother of forensic science.” Without her, the producers of CSI: Crime Scene Investigation wouldn’t have a show.

Frances is famous for creating exquisite dollhouses, but not ones you’d want to give your children. At first, you notice charming domestic scenes with lace curtains, striped wallpaper, wedding photos—then your eyes wander to the blood-spattered floors and dead bodies.

They’re simultaneously gruesome and useful, unsettling and enlightening.

Her dollhouses depict murder, and she used them to teach detectives to observe clues: “The inspector may best examine them by imagining himself a trifle less than six inches tall. He is seeking only the facts—the truth in a nutshell.”

They became known as the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death.

“A Lady Doesn’t Go to School”

Ostentatious wealth cocooned Frances Glessner Lee’s childhood.

Her father, John Glessner, made a fortune when his farm machine outfit merged with International Harvester, making it the fourth largest corporation in the U.S.

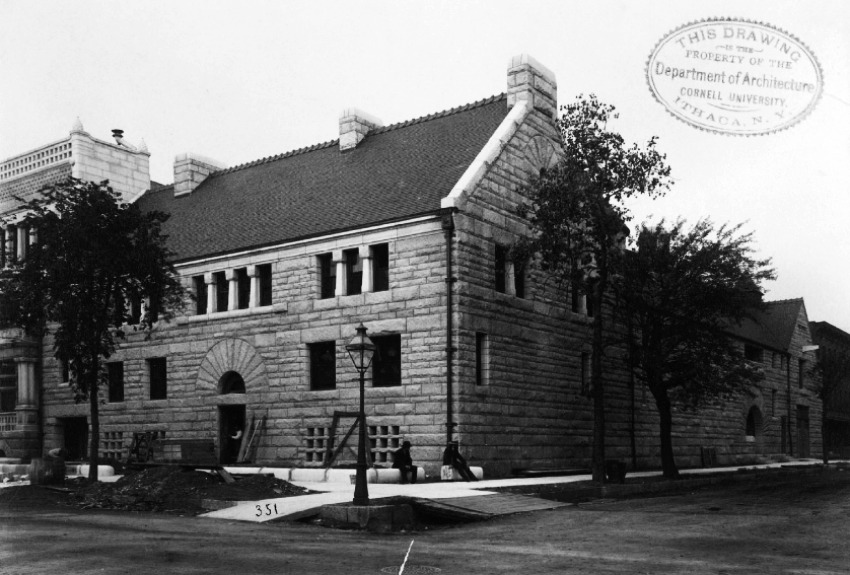

He and his wife prided themselves on their art and design aesthetic. When Frances was seven, Glessner hired architect H.H. Richardson to build a Gothic manse on Chicago’s most prestigious residential street, Prairie Avenue.

The neighbors, however, thought it resembled a prison. One critic described it as “pathologically private.” Frances and her brother George (seven years her senior) remained behind its thick walls, sheltered and home-schooled. Frances once declared to her mother, “I have no company but my doll baby and God.”

(The manse is now the Glessner House Museum. This weekend the museum celebrates fifty years since a forward-thinking group saved it from demolition. They purchased it for $35,000 in 1966.)

Like any upper-class Victorian girl, Frances learned the “female arts”—needlework, embroidery, interior design. She showed an unusual talent for crafting and painting miniatures. As a birthday gift for her mother, she created a detailed miniature of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

Her brother George escaped to Harvard at age 18 and Frances hoped to further her education, too. She desired to become a doctor or nurse, something of “value to the community.”

“A lady doesn’t go to school,” her father told her.

But Frances found a mentor in George Burgess Magrath (1870-1938), one of her brother’s Harvard classmates. Magrath was a medical student specializing in pathology.

They met one year when George invited Magrath to their thousand-acre summer home, The Rocks, in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. He came every summer after. Magrath and Frances often stayed up late into the night discussing unsolved murders, methods of detection, and of course, Sherlock Holmes, one of Frances’ favorite fictional characters.

Magrath became a brilliant professor of pathology at Harvard and a pioneer in the field of legal medicine. The two kept in touch over the years.

But at age 20, Frances bowed to parental pressure. She married lawyer Blewett Lee. Her father built them a house on Prairie Street a few doors down. (Her brother and his wife lived in the identical house next door.) The couple had three children, but after eight years of marriage, they legally separated.

Their divorce in 1914, when Frances was 36, caused a scandal simply because it wasn’t done.

“Luckily, I was born with a silver spoon in my mouth. It gives me the time and money to follow my hobby of scientific crime detection.” ~Frances Glessner Lee

Frances threw herself into forensic studies, reading thousands of texts and case histories.

In her late 40s, she became ill and spent several months recuperating. George Magrath, now a medical examiner, visited her each evening, regaling her with stories from his real-life crime scenes. He felt his field was degenerating, he confessed, for lack of skill. In many states, a coroner didn’t need medical training.

Journalist Pete Martin of The Saturday Evening Post observed:

“It’s not necessary for [a coroner] to know a tibia from a tuba, a choked drain from a choked windpipe. The only skilled knowledge he may have is how to play ball with the local political bosses. About the facts of violent death he may know precisely nothing.”

Frances asked how she could help. Magrath told her, “Make it possible for Harvard to teach legal medicine, and spread its use.”

Transforming Loss into Good

Frances’s brother George caught influenza and suddenly passed away in 1929. Her mother followed a few years later, leaving Frances, at age 51, her father’s sole heir.

In 1932, Frances Glessner Lee donated $250,000 to establish the country’s first Department of Legal Medicine at Harvard with George Magrath as its chair. A few years later, she created the Magrath Library of Legal Medicine with a thousand-volume bequest.

Family patriarch John Glessner died on January 20, 1936, a week before his ninety-third birthday. At age 58, Frances became one of the wealthiest women in the country. She moved to New Hampshire and took up permanent residence in a small cottage at The Rocks.

At first, Frances sold antiques and did needlework. But she’d never lost her enthusiasm for crime scene inquiry. (Many of the volumes she donated to Harvard came from her well-read personal collection.)

Then an audacious idea struck her. She could teach investigative skills by recreating crime scenes…in miniature.

The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death

Frances assembled her first “dollhouse of death” with the help of the estate’s carpenter, Ralph Mosher. “The Case of the Hanging Farmer” took three months to create.

It included strips of weathered wood Mosher obtained from a one-hundred-year-old barn. Mosher built the structures and some of the furniture, but Frances did the rest.

She sewed the clothes, glued on hair, and painted porcelain faces, always careful to mix the exact colors of blood and decomposition.

Little soup cans sit on shelves. Tiny half-smoked cigarettes rest in ashtrays. Mini-calendars tick off someone’s last days.

Frances and Mosher constructed three models each year, eighteen total. For her settings, she used actual police cases from the 1930s and 1940s. She donated the dioramas to Harvard.

Twice yearly Frances held “Nutshell Study” training sessions for forensic experts and homicide detectives from across the U.S. and Canada. She gave the participants 90 minutes to examine each model, instructing them to scan the room and note each detail.

In Nutshell No. 2, “Kitchen,” the oven gas jets are on. The door is locked from the inside. The windows are closed and locked, but the table cloth is askew. Newspaper fills the gaps around the door. A suicide?

But the female victim was baking a cake, an unlikely activity for someone considering suicide. An ice cube tray rests on the floor beside her, as if she’d been getting a cool drink for a visitor.

Today, most investigators would see a murder disguised as suicide. Back then, not so. We can thank Frances for championing the kind of detailed crime scene study that caught this woman’s killer. (In Nutshell No. 2, the woman’s estranged husband did, in fact, kill her, then tried to make it look like suicide.)

Frances Glessner Lee met Erle Stanley Gardner, author of the Perry Mason series, when he attended one of her seminars. He soon became a regular and a good friend. Gardner gave her autographed copies of all his books. (Frances’ granddaughter now cares for this priceless collection.)

He later wrote that “A person studying these models can learn more about circumstantial evidence in an hour than he could learn in months of abstract study.”

I didn’t do a lick of work to deserve what I have. Therefore, I feel I have been left an obligation to do something that will benefit everybody. ~Frances Glessner Lee

When Frances died at age 83, hundreds of officers, detectives, and coroners came from across the United States and Canada to honor her.

With her passing, Harvard’s endowment ended. The university put the dollhouses into storage. They probably would have ended up in a dumpster, except for Harvard professor Russell Fisher’s foresight. He contacted Frances’ estate for permission to borrow them for use in his new job as Maryland’s Chief Medical Examiner.

Today, the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death are permanently displayed on the fourth floor of the Maryland Office of the Chief Medical Examiner. Despite technical advances, they’re still used as training tools.

We can thank CSI: Crime Scene Investigation for reviving interest in her life and work. The Nutshell Studies inspired Season 7’s recurring villain, The Miniature Killer. The murderer leaves behind accurate dioramas of her crime scenes.

Susan Marks made a fascinating documentary about Frances that also explores our obsession with crime scenes called Of Dolls and Murder. You can rent it on Amazon here. The dollhouse photos in this article come from the film’s press kit.

And Guillermo del Toro is developing an HBO series about Frances based on Corinne May Botz’s excellent book, The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death.

Frances Glessner Lee’s story of wealth and isolation, defiance and subversion, creativity and dedication captures our imaginations.

What makes France Glessner Lee a compelling Later Bloomer?

Everything she learned, even the “female art” of miniature-making, came together in her 50s.

From that late-blooming synthesis, she transformed a whole field and became more than a value to the community. She became a force for justice.

Further Reading

- Murder in Miniature by Rachel Nuwer at Slate.com.

- Nutshell Studies: the extraordinary miniature crime scenes US police use to train detectives by Nigel Richardson