“There can be no happiness if the things we believe in are different from the things we do.” ~Freya Stark

My great-uncle Bob arrived in his 1958 Chevy Bel Air, dapper in a tweed suit and fedora. A diamond-studded elk’s tooth hung from his watch fob. He was his lodge’s Exalted Ruler.

I called him the “Grand Poobah,” bestower of gifts—an ammonite fossil, a piece of polished agate, a stamp from a faraway land. This Sunday he came bearing chocolate creme Oreos and a worn manila envelope.

He solemnly handed me the envelope and whispered, “Sailors of the Sky. Dragons in Distress.” I nodded, entranced. He’d brought the best treasure of all.

Dinner took forever. I sat and fingered the envelope under the table. Finally, my father sauntered to the sideboard and opened the bottle of brandy.

I looked hopefully at my mother. “Please, may I be excused?”

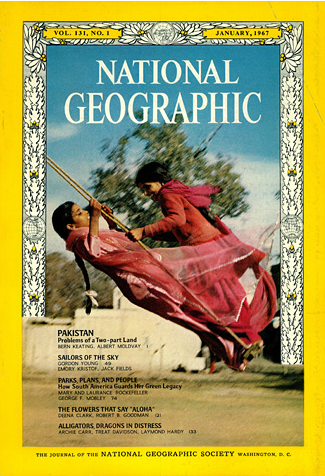

She nodded. Uncle Bob winked as I ran to my room with the envelope. I climbed onto the bed and slid out my treasure—National Geographic, January 1967.

On the cover, two girls flew into the air, red sarees like dragonfly wings. Did they represent Pakistan: Problems of a Two-part land? Did I want to know about them or Alligators: Dragons in Distress? And who were the Sailors of the Sky?

I studied the swinging girls. They looked about my age. I started reading, too young to grasp their problems. But I wanted to understand everything. National Geographic gave my childhood a sense of wonder, adventure, and purpose.

I wonder now if Freya Madeleine Stark (1893-1993) felt the same as she followed the exploits of Lawrence of Arabia.

I wonder now if Freya Madeleine Stark (1893-1993) felt the same as she followed the exploits of Lawrence of Arabia.

Freya Stark was an adventurer and explorer, memoir and travel writer, who taught herself Arabic, Farsi and Turkish.

But she grew up neither brave nor bold. At age 13, an accident disfigured her face. She escaped into 19th-century travelogues and dreamed of journeying into unknown lands, wrapped in scarves and robes, away from prying eyes.

Freya achieved her dreams and became so much more. She passed away at age 100, a Dame of the British Empire and author of over two dozen books.

By her own account, her life started at age 35.

Improbable Genteel Bohemians

Freya’s father and mother were first cousins. Robert Stark was born in England and Flora Stark in Italy. They met for the first time when Flora was 17 and married a year later. Robert had artistic aspirations and just enough money to keep his family in genteel bohemian style.

The story goes that Freya was born in Paris, where they studied art. They lived for a few years in Dartmoor, but Flora found it too dreary. They moved to Asolo in Italy, but Robert missed the English countryside. They had another daughter, Vera, and settled into a pattern of relocation and resentment.

When Freya was ten, her mother ran off with an Italian royal 19 years her junior. But the proposition was business, not passion. Count Mario wanted open a rug factory to employ his impoverished denizens.

He inflamed Flora Stark with his vision and she secretly financed it. When Robert found out, he exploded. Flora left him and took her daughters to Dronero, Italy to oversee the venture.

Much later, Freya wrote:

“My mother was so improbable. If I don’t explain, it looks very louche, and if I do it is rather brutal.”

Flora thrived with new-found power and responsibility, but her daughters became outcasts in the impoverished rural town.

One day Flora took the girls to see the factory’s new weaving machine. In the fashion of the day, both girls had knee-length hair. Freya wore hers loose. And she stepped too close.

Her hair caught in the mechanism and dragged her toward the ceiling. Someone ran to pull the switch, but Count Mario grabbed her feet and wrenched her down. Half of Freya’s scalp, her right ear and part of her eyebrow remained behind. She nearly died.

“People who have gone through sorrow are more sympathetic…not so much because of what they know about sorrow, but because they know more about happiness.” ~Freya Stark

Freya lay close to death for weeks. A young doctor performed an experimental surgery that took skin from her thighs and grafted it to her head—without anesthesia, with wasn’t yet in widespread use. She spent months recovering in the hospital at Turin. Friends sent gifts. She most enjoyed the maps and travelogues. She eventually returned to Dronero but forever felt disfigured.

At age 18, after years of drudgery as the factory’s bookkeeper, Freya finally escaped. Before emigrating to Canada, Robert Stark left both of his daughters a small bequest. Freya used hers to enroll at Bedford College, London—her first experience of formal education.

Like Edith Wharton, she’d been home-schooled by nannies in various countries and could speak several languages. But she considered England her home. She stayed at Bedford for two years, until World War I broke out. During the war, she trained as a nurse and took a post on the Italian front.

While Freya was at Bedford, her sister Vera had married Count Mario—a fate Freya had escaped by fleeing to England. From their correspondence, it seems Vera felt she had no choice. They owed him too much.

A Lunatic Obsession

“Some day I must make a list of the reasons for which I have been thought mad…it would make an amusing medley.”

Freya had made a few good investments. She bought a small farm away from Mario and took her mother with her. They barely subsisted without Mario’s patronage. Freya turned to flower farming and saved enough to put her dream in motion. She started studying Arabic with a Capuchin monk who lived in Beirut for 30 years before his retirement to the monastery. Everyone called it her “lunatic obsession.”

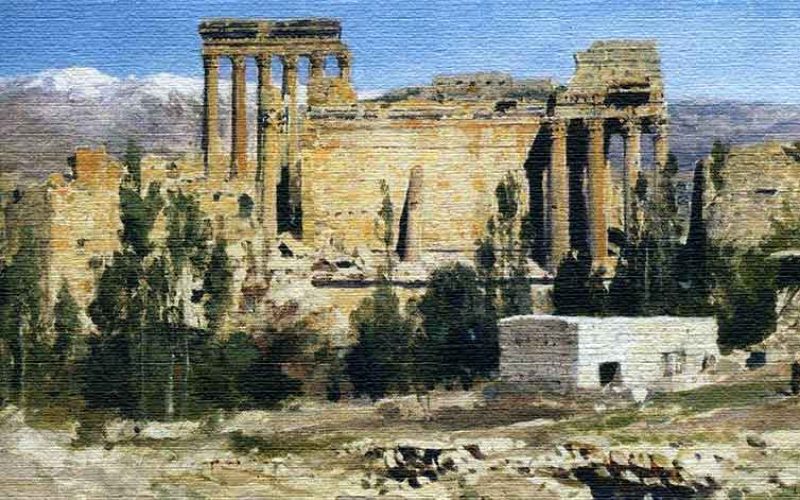

In November 1927, at age 35, Freya embarked for Lebanon to continue her language studies. She also spent time in Damascus. Then, with a friend and native guide, she ventured to Jabal Druze, or Mountain of the Druze, then under French martial law.

The Druze were a heretical branch of a heretical branch of Shia Islam. They didn’t like strangers. But Freya carried an introduction from her Lebanese tutor. His childhood nurse had been a servant to the Druze chieftain.

The French came upon them and detained them for several days, certain Freya and her party were spies for someone. Of the experience, Freya later wrote:

“The great and almost only comfort about being a woman is that one can always pretend to be more stupid than one is and no one is surprised.”

They were finally released. The Druze, discovering that they were hereditary enemies of the French, welcomed them.

Distance, History, and Danger

“I wanted space, distance, history and danger, and I was interested in the living world.”

Two years later, Freya returned to the Middle East, this time journeying into Luristan, a remote part of Iran famous for its black market bronzes. She was the first European woman to venture there. Her biographer, Jane Fletcher Geniesse, writes:

“Enduring hunger, gale winds, nights on rocky terrain, and a guide who appropriated her Burberry coat and fell to praying when dinner had to be got, Freya encountered dervishes, idol worshipers, and armed tribesmen; attended both weddings and dyings; and attempted to scamper with ibex on the side of a nine-thousand-foot-high mountain.”

In 1933, now 40, Freya returned to Italy a different woman. She’d slept with nomads and wandered with shepherds. She pondered colonial rule and concluded that most people, given a chance, would prefer to govern themselves. She’d found her calling. If she had to sell flowers for the rest of her life to finance her trips, so be it.

But then everything changed. Freya’s mother met her at the station. A letter had arrived from the Royal Geographic Society. They wanted her in London to receive a prize for her travels in Luristan: “We have profited greatly by your literary talent and the attention you have paid to getting accurate transcript of the names along your routes, contributing to the correctness of our maps…”

During her RGS acceptance speech, Freya discovered she had a charismatic talent for public speaking. The BBC invited her to lecture and four publishers wanted her to write a book. She chose John Murray, who’d published all the legends, including Byron, Darwin, and Sir Walter Scott.

In 1934, The Valley of the Assassins came out and made Freya an instant celebrity. Her self-effacing and conversational writing style brought her a great following. From then on, the RGS financially supported her explorations, and John Murray published them.

In her 60s, Freya followed Alexander the Great’s footsteps and wrote three books about her journeys: The Lycian Shore, Ionia: A Quest, and Alexander’s Path.

Dame Freya

At age 82, Freya a Dame of the Realm. She decided to publish her letters, all sixty years’ worth. John Murray balked. Freya sold some Yemeni silver jewelry and a few paintings and published the letter herself, eight beautiful leather-bound volumes.

At 85, her driver’s license was revoked. No matter, she retired to her Italian hill town and did errands by horseback.

Freya died in 1993, at age 100. Once, when asked how she felt about death, she replied,

“I feel about it as about the first ball, or the first meet of hounds, anxious as to whether one will get it right, and timid and inexperienced—all the feelings of youth.”

A Personal Epilogue

Several people remarked on the vividness of my opening story. Freya’s recognition by the Royal Geographic Society turned her life around. I likened it to my love of National Geographic magazine. But why that particular memory and year?

In August 1967, I was playing at a construction site with some friends. I fell from a cinder block wall and was impaled on a 4-foot tall iron rebar. It went through my inner thigh. Cutting it out would leave me paralyzed or worse. The hospital found a U.S. Army shrapnel specialist 200 miles away and helicoptered him in. In an experimental 8-hour surgery, he saved me.

During my first week of recovery, uncle Bob arrived at my bedside with his National Geographic back issues. He solemnly informed me that he’d started a subscription in my name.

He renewed it every year until his death a decade later.

Source

Passionate Nomad: A Life of Freya Stark by Jane Fletcher Geniesse.