“Painting is not the important thing. The important thing is keeping busy….If I hadn’t started painting, I would have raised chickens.” —Ann Mary Robertson

She started painting at age 78 and sent her early works, along with her raspberry jam, to the Cambridge county fair. The jam won a ribbon. No one noticed the paintings.

But she persevered and painted thousands more, 25 after she turned 100. By then, some were worth $10,000. Now they go for a million.

Anna Mary Robertson was born before Lincoln took office. She died the year of JFK’s inauguration.

Until her 101st birthday, she painted every day. You might know her as Grandma Moses.

A Life From Lincoln to Kennedy

Anna Mary Robertson (1860-1961), also known as Grandma Moses, lived from Civil War’s onset to the Civil Rights Movement.

Though born on a farm in Greenwich, New York, her parents filled her early years with creative projects. They bought large sheets of blank newsprint for a penny and gave them to Mary and her siblings to draw on. “It lasted longer than candy,” she recalled. But her real artistic impulses would wait another 65 years.

She took her first job at age 12, cooking and cleaning for rich neighbors. She spent the next fifteen years working for wealthy families, until she caught the eye of Thomas Moses, a hired hand at her farm. They wed and became tenant farmers in Virginia.

Mary Moses gave birth to ten children over the next twenty years. Five died as babies. She used her own money to buy a cow, then made and sold butter to help with expenses. By 1905, Mary and Thomas bought their own farm in eastern New York and it did well.

Thomas Moses died of a heart attack in 1927, when Mary was 67. Her youngest son Hugh and his wife took over the farm. Grandma Moses, as they called her, lived with them. She picked up embroidery to keep busy until rheumatism made it too hard to hold a needle. At age 78, she started painting instead.

“I had always wanted to paint, I just didn’t have time until I was 78.”

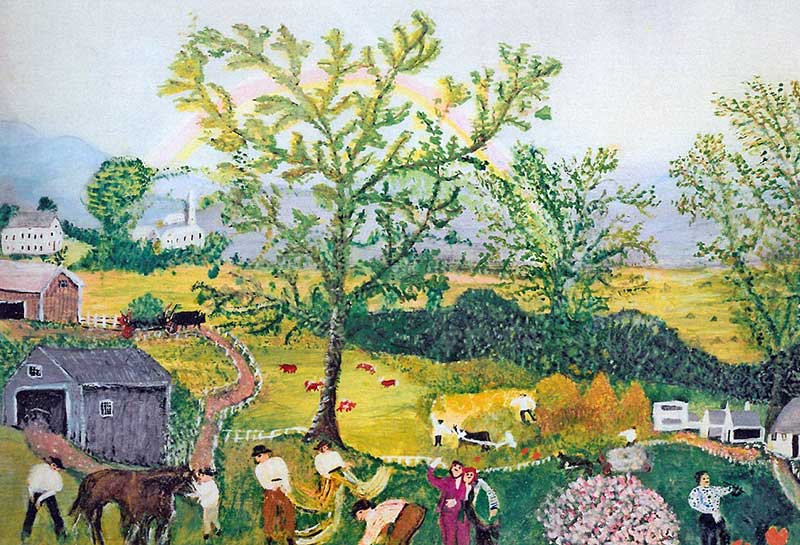

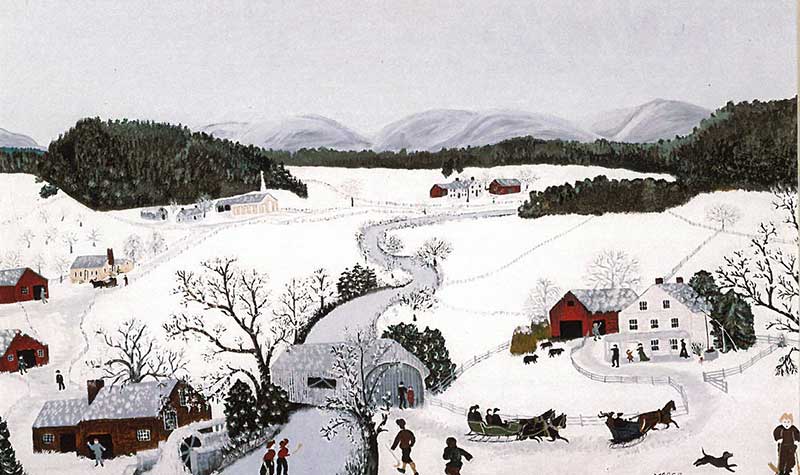

As first Grandma Moses copied prints and old post cards. You can see the Currier & Ives influence in her early works. But soon she created original scenes drawn entirely from childhood memories.

For two years, her paintings gathered dust at the local drugstore until art collector Louis Caldor meandered through town on holiday. Caldor bought all the drugstore’s paintings, then visited Grandma Moses to buy more.

For a year, Caldor tried to drum up interest in her work. He entered three paintings in a New York Museum of Modern Art Exhibition called “Contemporary Unknown American Painters” with great success.

Yet Caldor couldn’t find gallery space for her. When owners learned she was 78, they balked. Most felt she wouldn’t live long enough to recoup the cost of organizing a show. She would paint for twenty-one more years.

“A primitive artist is an amateur whose work sells.”

Caldor finally persuaded art dealer Otto Kallir, a Viennese immigrant, to give her chance. “What a Farm Wife Painted” made Grandma Moses the darling of the art world and the American public. Her simple, happy paintings created a yearning for the world before war and depression.

In 1946, sixteen million Grandma Moses Christmas cards sold. In 1953, Time magazine featured her on its cover.

In 1955, at age 95, she appeared on See It Live! with Edward Murrow. She couldn’t have imagined television as a child. Yet onscreen, she’s completely self-assured.

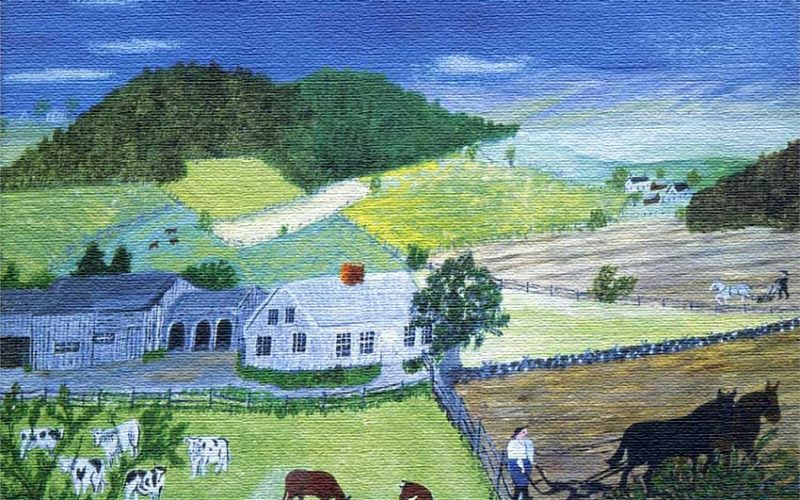

“Anyone can paint,” she tells Murrow. She demonstrates her technique—”first the sky, then the mountains, then the hills, then the trees, then the houses, then the cattle and then the people”—and hands the brush to Murrow.

He botches it, trying to balance the paintbrush and a cigarette in the same hand. She smiles at the camera.

She charmed wherever she traveled. Newspaper accounts called her “cheerful as a cricket” and described her “mischievous gray eyes and a quick wit.”

New York Governor Rockefeller proclaimed her 100th and 101st birthdays “Grandma Moses Days.” She died a few months after her 101st. Her doctor said, “She just wore out.”

New York Governor Rockefeller proclaimed her 100th and 101st birthdays “Grandma Moses Days.” She died a few months after her 101st. Her doctor said, “She just wore out.”

As a child, I remember studying her paintings. “I can do that,” I thought. I didn’t get it then. Now, looking at her scenes and luminous color choices leaves me feeling peaceful and nostalgic. It wasn’t her technique that made her famous and well-loved, but the era and the emotions she evoked.

Even if she hadn’t attained fame, Grandma Moses would have kept painting.

She allowed her arthritic “disability” to shape how she held a brush and expressed her memories. Her two-decade career rivaled that of many younger artists.

Perhaps more than anyone else, this self-taught farm girl proved the phrase “it’s never too late” a rich source of hope.

I look back on my life like a good day’s work, it was done and I feel satisfied with it. I was happy and contented, I knew nothing better and made the best out of what life offered. And life is what we make it, always has been, always will be. ~Grandma Moses

Sources

- Grandma Moses’ Obituary in the New York Times.

- Opening Artwork: The Plowboy by Grandma Moses (1950)