Imagine Paris, 1871.

Your day job—to search each wagon that arrives at the city gates for certain contraband.

“Bonjour,” you say, “Do you carry wine, bread, or cheese for consumption in the city?”

That, of course, rates as the most idiotic question anyone could pose to a Frenchman.

“Mais, no!” the driver cries.

You pull a baguette from under his seat. The driver gives you a dirty look and pays tax on the hapless loaf. The next wagon trundles forward.

You sigh. You’re not a very popular guy.

And that’s what poor Henri Rousseau (1844-1910) experienced, day in and day out, for years.

But all that repetition allowed one thing to run wild—his imagination.

Rousseau drifted through a few years of law school, then joined the army. But he took responsibility for his mother’s care when his father died.

They moved to Paris in 1868 and Rousseau (like many late bloomers, including PD James and Richard Adams) joined the civil service and eventually became a high-ranking customs official. In 1869, he married Clemence Boitard, his landlord’s daughter. It must have been a grand passion, for he wrote a waltz named after her. They had four children, but three died very young.

Around 1884, at age 40, Rousseau first picked up a brush.

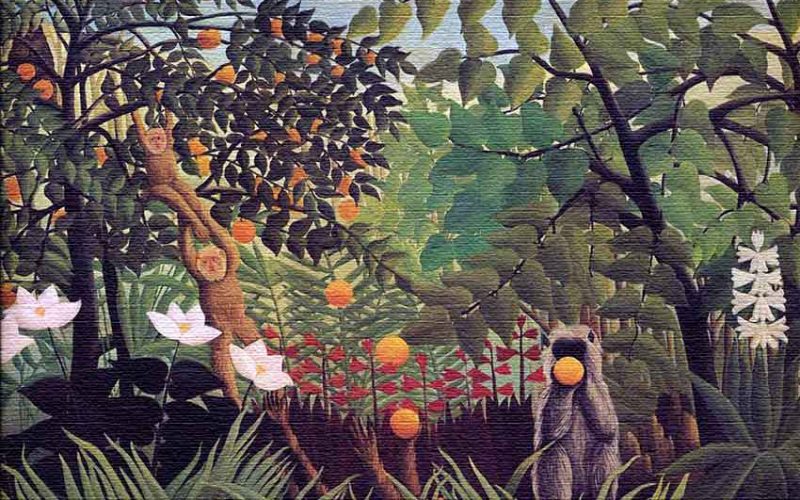

He painted landscapes of the mind, since he never visited the locales he depicted. His knowledge of jungles and animals entirely came from books, the zoo, a museum of taxidermy.

I imagine him imagining scenes like the one at right when he encountered a particularly belligerent wagon driver.

Rousseau submitted his work to the official Salon, the high arbiter of art, but they rejected him for lack of skill and perspective.

He kept painting.

A few years later, he applied to the newly-formed Salon des Independents, which welcomed all artists, irrelevant of skill and public opinion.

But even among these “independents,” his complete disregard for artistic convention brought ridicule.

In 1888, Clemence died, leaving Rousseau heartbroken. Perhaps he felt that life was just too short, for he took early retirement four years later.

At age 49, Rousseau started painting full-time.

He didn’t achieve instant success. Most exhibitions he applied for rejected him. The mayor of his hometown destroyed a portrait commissioned from Rousseau, he hated it so much.

At one point, Rousseau took part-time work selling Le Petit Journal and offered drawing lessons.

And for the rest of his life, he was called “Le Douanier” or “the customs man.” But Rousseau never gave up. He continued to paint prolifically.

He died in 1910 at age 66, an icon to the next generation of rebellious artists. A year after Rousseau’s death, the official Salon held the first exhibition devoted exclusively to his work.

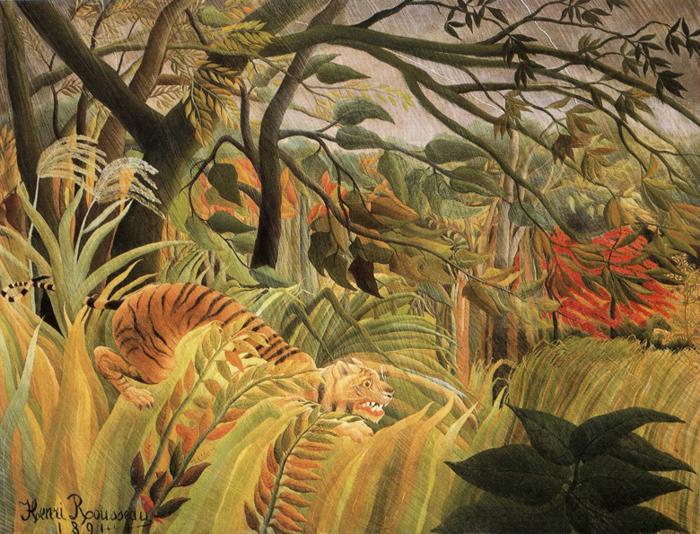

Adrian Searle of The Guardian concludes,

Rousseau’s appeal is to the child in all of us. He gives us back a sense of wonder. But like all the best children’s stories, his works are full of darkness, violence and mystery. This is why he’s worth returning to, and why he is so popular. Rousseau himself remains the biggest mystery of all.

More About Henri Rousseau

- The Guardian UK: Stumble in the Jungle