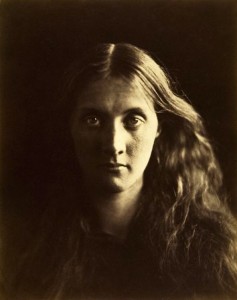

Do you recognize this model? At age 9, she was the shy muse of a stammering Oxford professor named Charles Dodgson.

By age 20, she’d become a minor celebrity who’d spent much of her life in front of a camera. Here’s one more clue:

Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.

As you’ve probably guessed, she’s Alice Liddell, the girl who inspired Lewis Carroll (Dodgson’s pen name) to write Alice in Wonderland. She didn’t count photography an impossible thing.

But for Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879), the woman who created this portrait, photography was the most wondrous invention in the world.

Who has the right to say what focus is the legitimate focus?

~Julia Margaret Cameron

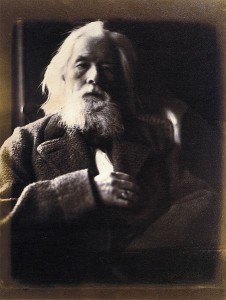

Julia was born in Calcutta, India, to a French mother and a British father who worked for the East India Company. Her peers considered her the eccentric “ugly duckling” among six gorgeous sisters.

She spent most of her childhood in France with her grandmother. When she was twelve, French inventor Nicéphore Niépce captured the first photograph, a camera obscura image projected on a pewter plate coated with bitumen varnish.

Julia returned to India, and at age 23, married Charles Hay Cameron, a member of the Law Commission stationed in Calcutta. He was twenty years her senior. Ten years later, the government forced Charles to retire, partly because he advocated education for the children of India.

The family moved to London, where one of Julia’s beautiful sisters, Sarah Prinsep, hosted a salon for famous artists and writers. There, Julia met Alfred Lord Tennyson, who became a life-long friend.

In 1859, Julia and her husband visited the Tennysons at their home on the Isle of Wight. They fell in love with Freshwater, a village on the island, and purchased a house there. They called it Dimbola Lodge after the coffee plantation Charles had purchased in Ceylon to provide retirement income.

Four years later, the plantation began to fail. Charles returned to Ceylon to oversee it. For her birthday that year, Julia’s daughter gave her a camera so it might “amuse you, Mother, to try to photograph during your solitude.”

Julia was 48 years old. She taught herself to use the equipment and chemicals involved in collodion or wet-plate process. It required that photographic material be coated with light-sensitive silver salts, then exposed and developed within the span of about fifteen minutes.

It was no trite hobby for a bored society matron.

Julia’s Famous Portraits

During the next decade, the camera became Julia’s muse and medium:

From the first moment I handled my lens with a tender ardour, and it has become to me as a living thing, with voice and memory and creative vigour.

Through her sister and Tennyson, she had met many of Victorian England’s greatest minds, including Robert Browning, Charles Darwin, and Sir John Herschel. Now they became her models, as did her pretty Freshwater neighbor, Alice Liddell.

Darwin became Julia’s first paying client and Herschel, her technical adviser. Herschel, the age’s foremost astronomer, also made several contributions to photographic science, including the use of light-sensitive salts.

“Pray!” he would write her and “Be more cautious!” Julia replied that she “felt [her] way literally in the dark thro’ endless failures.”

Another one of Julia’s favorite subjects was her niece and namesake, Julia Prinsep, who later became Julia Stephen, mother of Virginia Woolf.

In August 1874, Tennyson commissioned her to create photos for the People’s Edition of The Idylls of the King. Although she captured two hundred images, the publisher only selected two.

Unfazed, Julia self-published a companion volume entitled Illustrations to Tennyson’s Idylls of the King, and Other Poems, with images made directly from her negatives.

She developed her unique style by accident, the result of a short lens and long exposure. It focused the center of the portrait and blurred the background. She liked the effect and reproduced it again and again.

Her contemporaries ridiculed her. The Photographic Journal, reviewing her submissions to the annual exhibition of the Photographic Society of Scotland in 1865, wrote:

Mrs. Cameron exhibits her series of out-of-focus portraits of celebrities. We must give this lady credit for daring originality, but at the expense of all other photographic qualities.

But her style influenced modern photographers and “soft focus” still dominates portrait photography.

In 1875, the Camerons moved to the plantation in Ceylon. Julia caught a chill and died there four years later. Some biographers speculate that sixteen years of inhaling photographic chemicals might have weakened her lungs and contributed to her death.

But somehow I don’t think she’d do anything different.

When she discovered her calling at age 48, she’d already raised eleven children—five of her own, five orphaned relatives, and a beautiful Irish orphan whom she employed as a model and saw married to a handsome gentleman.

She cared for her elderly husband (who survived her by two years) and ran a busy household.

Julia Margaret Cameron also mastered an invention that didn’t exist until she was twelve.

I find it exciting to think there might be something out there, yet to be invented, that will become the calling of another late bloomer.

Sources

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Julia Margaret Cameron Trust at Dimbola

- The New Yorker

- Opening Image: Alice Liddell in 1872 by Julia Margaret Cameron.