In 1699, more than a century before Charles Darwin explored the Galapagos, a middle-aged woman sailed from The Netherlands to South America to study the region’s insects. Most people considered her voyage bizarre in the extreme, especially for a woman.

It was a time of great religious upheaval. Just a few years earlier, women were burned as witches in the New World. Insects had a reputation as minions of the devil.

Plus, no one understood how insects reproduced. The act seemed slightly unsavory since it often involved dirt, dung, or rotting food.

The prevailing theory, called “spontaneous generation,” held that insects sprung from the marriage of matter and one of the elements. With the help of water or sunlight, wool somehow gave birth moths, cheese to worms, cabbage to caterpillars.

So what inspired botanical artist Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717), age 52, to follow her weird across the vast and dangerous sea to study this misunderstood Kingdom of Animals?

We’ll never know. If Maria left us clues, they’ve been lost in time. But her astonishing illustrations speak for themselves.

I. Egg

A 17th-century wife’s tale says that whatever a woman noticed while pregnant would imprint on the child. Maria Sibylla Merian’s mother remembers gazing upon an unusual collection of bugs.

Her father, Matthaus Merian, owned a publishing house in Frankfurt known for its beautiful illustrations, which Merian engraved himself. When Maria was three years old, he passed away and left the business to his sons by an earlier marriage, Matthaus Jr. and Caspar.

From a corner of their studio, Maria sat for hours watching them create copper engravings of maps and exotic species.

Maria’s mother Johanna remarried almost immediately (not unusual when women had few legal ways to earn a living). Her new husband, botanical artist Jacob Marell, encouraged Maria’s talent. She learned to paint flowers alongside his apprentices and another set of half-brothers.

But Jacob and Johanna separated when Maria was twelve, though he provided some financial support.

Maria continued drawing, but she also became obsessed with insects. She began to catch specimens and observe them. She even hunted down a silkworm and documented its life cycle. People considered Maria’s interest so strange, her mother could only relate that old wife’s tale.

In 1662, when Maria was 15, she obtained a copy of Metamorphosis Naturalis from her half-brothers.

The book illustrated insect metamorphosis for the first time and explained how anyone could conduct experiments. (Something all school children do today.) Maria collected jars of caterpillars, kept notes, made illustrations.

She considered the work a “great drudgery,” tedious and time-consuming—until that moment when a butterfly unfurled its iridescent wings.

II. Caterpillar

A year later, one of her stepfather’s apprentices returned to the shop after a European study tour. At age 28, Johann Graff was ready and become master of his own studio. But Guild membership required him to marry.

Who better than the talented step-daughter of his old mentor?

We don’t know how Maria felt about marrying someone twelve years her senior. Perhaps it was love, perhaps a practical collaboration since Graff could complete her training.

There’s no doubt that, at some point, Maria became a master in her own right.

Between 1675 and 1680, Maria’s first work, The Book of Flowers, was published in three volumes. She conceived it for maximum use and financial profit, painting flowers and leaves so that none touched each other. It became the perfect pattern book for “artists, embroiderers on silk, and cabinetmakers,” according to the Getty Museum.

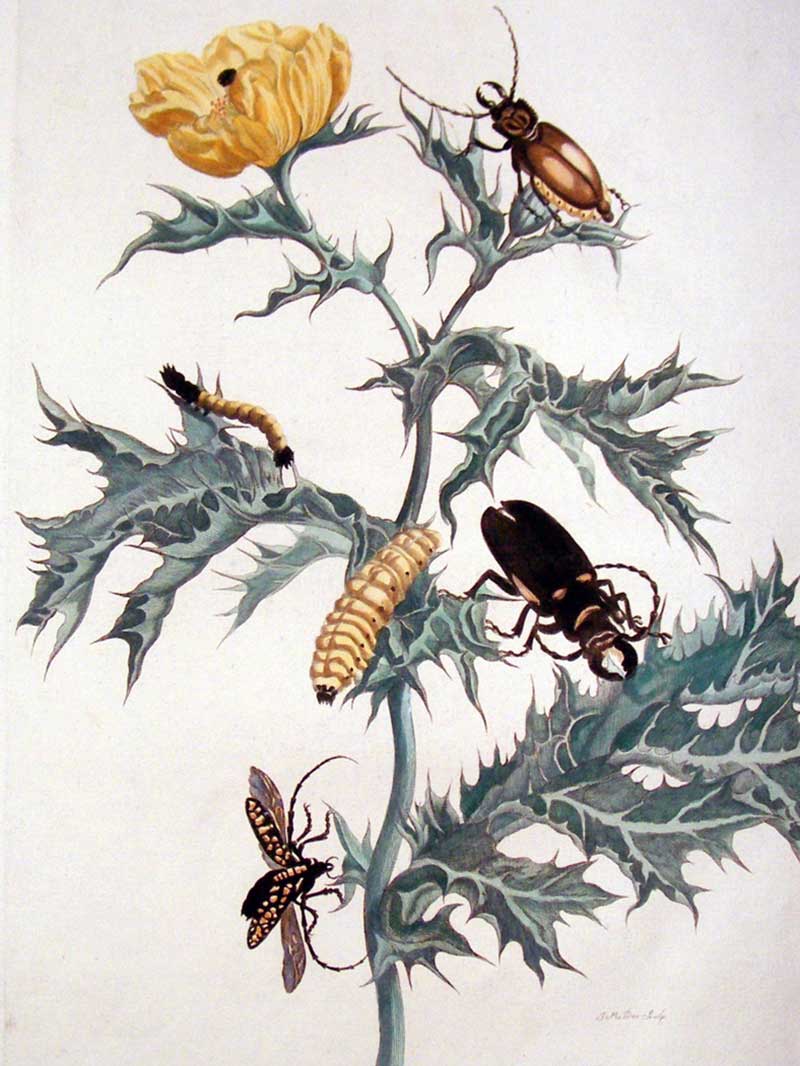

In 1679, Maria published Caterpillars: Their Wondrous Transformation and Peculiar Nourishment from Flowers, later considered a “major advance in entomology.”

But something was clearly wrong at home. In an age where most couples had several children, Maria gave birth to two daughters a decade apart—Johanna Helena in 1668 and Dorothea Maria in 1678.

In 1685, after twenty years of marriage, she abruptly left Johann Graff. A contemporary newspaper cites Graff’s “shameful vices” as the reason, which might explain her next move.

With her mother and two daughters (Dorothea was now seven and Johanna seventeen), she journeyed to The Netherlands, where her half-brother Caspar had joined the Labadists, a religious sect who valued celibacy.

The Labadists lived behind a high Gothic gate in Castle Waltha, far away from the local village, whose inhabitants called them “People of the Woods.” Families shared a single room. Monitors roamed the halls dispensing beatings to the impious. In order to join, supplicants gave up all possessions and donned coarse wool habits.

Stripped of her drawing tools, Maria continued her studies in the herb garden, contemplating the life cycles of “God’s lowliest creatures” whom she loved.

In 1690, Maria’s mother passed away. Her brother Caspar had died a few years earlier. And, although the sect “preferred” celibacy, a few teenage girls mysteriously became pregnant.

Maria Sibylla Merian requested the return of her possessions, took her daughters, and quit Castle Waltha.

III. Chrysalis

She chose Amsterdam as their refuge.

The Netherlands had recently become an international power, rivaling Portugal in the spice trade and challenging England on the sea. The Dutch East India company set up colonies in the Americas, Indonesia, and Africa. Amsterdam was a center of trade, art, and knowledge.

Women could own businesses, keep property, and become apprentices. Maria and her daughters had alighted upon the perfect environment.

They met other female artists, established their own studio (by then, the girls had apprenticed to their mother), and found several benefactors.

Within a few years, Maria flourished creatively and financially. Her eldest daughter Johanna set up shop, married a successful businessman with New World connections, and moved to Suriname with him.

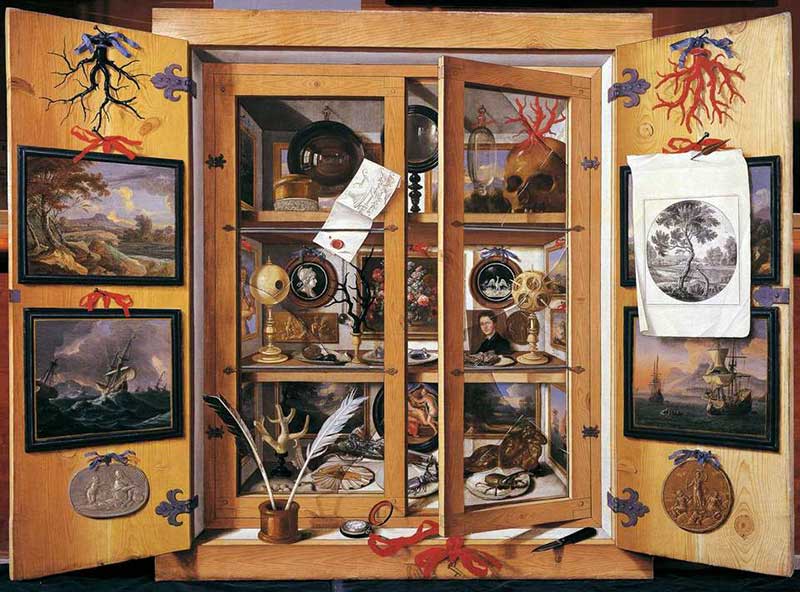

Amsterdam was also home to Europe’s foremost “Cabinets of Curiosities,” called in German Wunderkammer or “wonder-rooms.” Before scholars classified biology, archeology, paleontology, and the other natural sciences, they displayed objects together thematically and concocted elaborate stories to explain them.

A manatee’s flipper became a mermaid’s hand, a chunk of ambergris the philosopher’s stone, a narwhal tusk proof that unicorns once lived.

Maria soon befriended Dr. Frederik Ruysch, a pioneer in embalming, whose wonder-rooms displayed skeletons and body parts alongside fossils, stuffed birds, exotic plants, and more importantly, insects imported from Amsterdam’s trading colonies.

So Maria had access to the best insect collections in Europe, but she found the displays troublesome. The desiccated bugs, skewered on pins and placed in random dioramas, told a confusing and incomplete story.

Where did they live? What did they eat? What were their life stages?

Maria Sibylla Merian wanted to continue her insect studies, but bustling Amsterdam lacked the one thing she needed. She observed,

In Holland more than elsewhere I lacked the the opportunity to search specifically for that which is found in the fens and heath.

IV. Butterfly

In 1699, eight years after she moved to Amsterdam, Maria placed a newspaper ad offering 255 of her paintings for sale.

Her plan—to raise money for a scientific expedition to the Dutch colony of Suriname (where Johanna had settled), and paint on location the curiosities she’d seen in cabinets.

It was a stunning, audacious idea, but Amsterdam gave her a grant, the first-ever to a female explorer. Her younger daughter Dorothea accompanied her. The grueling voyage took three months.

(One can imagine Maria, confronted by grubs in her food, simply slipping them into a matchbox for further study.)

She and Dorothea found a hut in the capital of Paramaribo, a town of mixed native and colonial architecture. They slept in hammocks, grew their own vegetables, and collected water in cisterns.

They’d roughed it with the ascetic Labadists. Suriname must have seemed like paradise in comparison.

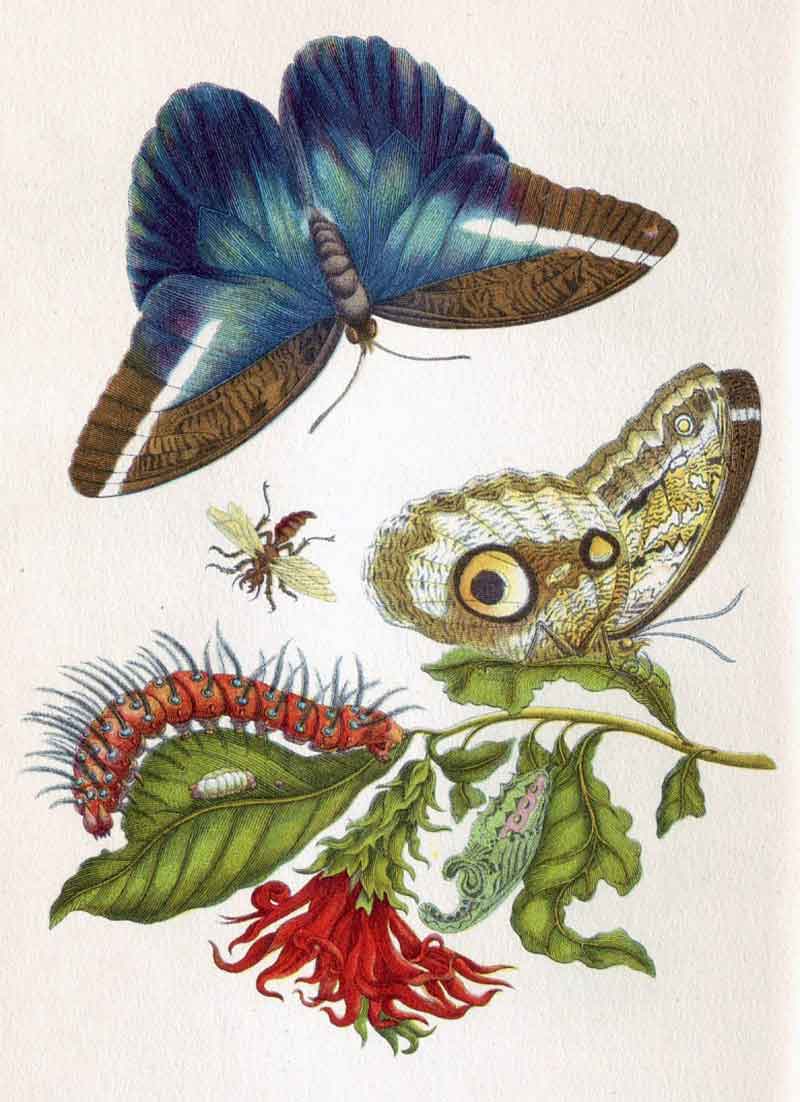

For Maria, Suriname represented the vibrant outdoor classroom of her dreams. Through her son-in-law, she received permission to visit local plantations in search of specimens. At one, she found a fat white caterpillar with red hair spiking from its back.

Lovely, but nasty. Its poisonous spikes break off in the skin and cause a painful rash. Somehow she got it into her box without injury. But mostly she could watch “new metamorphoses” right in her back yard.

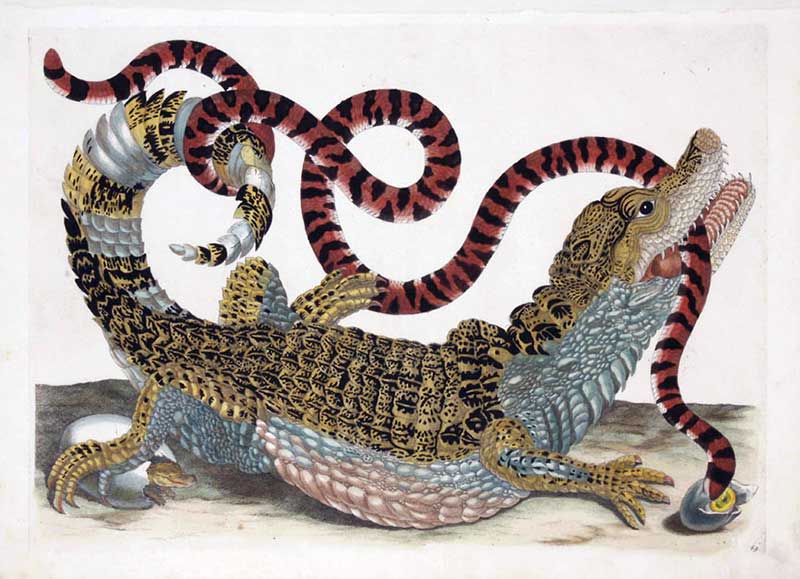

Eventually, she and Dorothea ventured into the jungle, canoeing up the Suriname River with a guide, since trees stood too densely to travel overland. Hearts pounding, they glided around anaconda, piranhas, and caimans.

Maria painted a stunning watercolor of a caiman locked in combat with a snake, a study in the grim and awe-some reality of nature.

After two years of exploration and painting, Maria came down with life-threatening malaria. She and Dorothea reluctantly packed their specimens in brandy (with a silent prayer the cabin crew wouldn’t drink them) and sailed home.

Back in Holland, Maria contemplated recouping her investment by selling her paintings to rich buyers. She wrote:

…they would be worth the money and the expenses of the journey due to their great rarity, but then only one person would have them.

She came from a family of engravers and bookbinders, so she decided to create multiple editions “for the benefit and pleasure of scholars and lovers of such things.” In 1705, Maria published Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium in both Dutch and Latin.

The book didn’t sell as well as she’d hoped, but it brought her recognition during her life and long after. Russian emperor Peter the Great, one of her fans, bought most of her collection after her death at age 70.

What makes Maria Sibylla Merian Such a Compelling Late Bloomer?

She never lost her sense of curiosity and unconventional vision, even while enduring a painful marriage and a spartan monastic sojourn.

She was the first woman to organize a scientific expedition and to receive a scientific grant, both after age 52. She was one of the first artists to portray the relationships and life cycles of animals in their natural settings. She doggedly followed her weird.

One hundred and fifty years after Maria’s death, scientist Ernst Haeckel coined the term “ecology” for the study of relationships among organisms and their environment throughout their life cycles.

Today, Maria Sibylla Merian would be most proud that many scholars considered her the world’s first ecologist.

Where will your midlife voyage of discovery take you?

Sources

Chrysalis: Maria Sibylla Merian and the Secrets of Metamorphosis by Kim Todd. Mariner Books, 2007.

“Maria Sibylla Merian: The First Ecologist?” by Kay Etheridge in V. Molinari and D. Andreolle, Editors, Women and Science: Figures and representations—17th century to present, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle upon Tyne (2011).

And you might have noticed, Maria is the inspiration for my 10th anniversary web redesign.