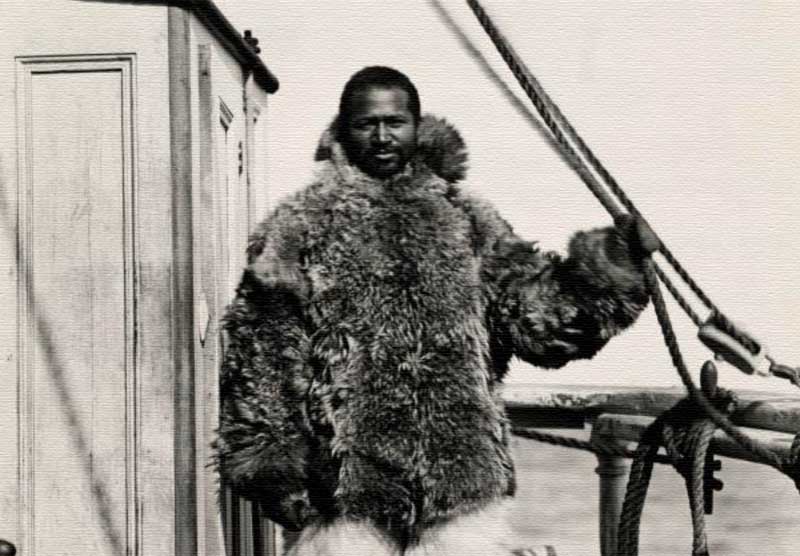

Matthew Henson was born to Black sharecroppers on August 8, 1866, a year after the Civil War’s end. At age 13, he walked to Maryland where he found work as a cabin boy on a ship bound for China.

He led a life of adventure and adversity, loyalty and betrayal, recognition and obscurity, that took him to the Arctic’s frigid reaches and back. Many people, if asked, would tell you that Robert E. Peary “discovered” the North Pole.

But there’s a good chance Matthew Henson deserves that accolade.

Matthew Henson’s Early Years

Henson was the son of freeborn sharecroppers with a farm near the Potomac River in Maryland, a border state of slave-holders that nominally stayed in the Union. But that didn’t stop racial violence from taking over after the war.

When Henson was four, his father moved the family to Washington, DC for safety. His mother died not long after and his father passed away when Henson was 10. He went to live with an uncle who died two years later.

At age 12, Matthew Henson walked to Baltimore and found work as a cabin boy on the merchant ship Katie Hines, bound for China. The ship’s captain taught Henson to read, write, and navigate. Over the next six years, Henson journeyed to Japan, Manilla, North Africa, Spain, France, and through the Black Sea to Russia. He became a superb seaman and developed a facility for learning languages. But when he was 18, the ship’s captain passed away.

Bereft of his mentor, Henson returned to Washington, where he found work in a clothing store. Three years later, Lt. Robert Edwin Peary, a Navy surveyor, walked in to buy a sun helmet for his upcoming expedition to Nicaragua. The two struck up a conversation.

Upon discovering Henson’s sailing and navigation skills, Peary hired him as his “valet” for the trip. Thus began a partnership that would last more than two decades.

The 1891-1909 Polar Expeditions

Lt. Robert Peary was obsessed with fame. The North Pole was one of the last unexplored regions of the earth, and he was determined to make his mark there. In 1886, he wrote to his mother,

…remember, mother, I must have fame, and I cannot reconcile myself to years of commonplace drudgery and a name late in life when I see an opportunity to gain it now.

Henson had made himself so invaluable in Nicaragua, Peary knew he’d need him in the Artic. And he was dead on. Not long after they arrived in Greenland, Peary broke his leg in an accident with the ship’s tiller.

During Peary’s six-month recovery, Henson became the expedition’s leader in everything but name. He also started learning the Inuit language and mastered dog-sled driving. These efforts and his superb hunting skills made Henson a favorite with the Inuit.

They called him Mahri-Pahluk, meaning “Matthew the Kind One.” Later he wrote in his memoir, A Negro Explorer at the North Pole,

Many and many a time, for periods covering more than twelve months, I have been to all intents an Esquimo, with Esquimos for companions, speaking their language, dressing in their clothing…I have come to love these people. I know every man, woman, and child in their tribe. They are my friends and they regard me as theirs.

On this trip, Peary recovered enough to explore farther north, and confirmed that Greenland was an island.

Peary’s 1893-1895 expedition to chart Greenland’s ice cap ended in failure. Peary, Henson, and their crew almost starved. They contracted scurvy after eating canned food that was eighteen years old and had to kill some of their sled dogs to survive.

Their 1898-1902 attempt proved equally disastrous. The treacherous ice pack blocked their progress north and they lost six Inuit team members.

The 1905-1906 trip fared better. Backed by President Theodore Roosevelt and awarded a vessel that could cut through ice, the team sailed within 175 miles of the North Pole. Again, melting ice forced them back.

On February 28, 1909, after months at sea, Peary began his final assault on the North Pole. He was 53 and Henson was 43, so it was now or never. He divided his men into teams. The first group traveled ahead, cached supplies, then turned back. The next group “leap-frogged” over the previous position and did the same.

On April 6, Peary selected Matthew Henson and four Inuit to make the final run with him:

Henson must go all the way.

I can’t make it there without him.

Peary rode prone in a separate sled since he had difficulty walking. On a previous expedition, he’d lost eight toes to frostbite. He sent Henson ahead to cut a path for him through the rough ice. But Henson accidentally overshot and crossed the Pole.

Peary arrived 45 minutes later and knew he’d been upstaged. The next morning, he got up and departed without speaking to Henson. For his part, Henson always supported Peary’s claim to the North Pole, even when it came under fire. But the two men were never close again.

In 1909, the National Geographic Society awarded Peary their highest honor, the Hubbard Medal.

While Peary’s star rose, Henson dropped into obscurity. He spent the next three decades working as a US Customs clerk. But in 1937, when he was 70, the prestigious New York Explorers Club made him an honorary member. Seven years later, Congress finally awarded him the Peary Polar Expedition Medal.

Matthew Henson passed away in 1955 at age 88. He was buried at New York’s Woodlawn Cemetery. A few months before his death, he divulged his secret to The New York Times:

I was in the lead that had overshot the mark a couple of miles. We went back then and I could see that my footprints were the first at the spot.

Not The End

The appendix of Matthew Henson’s memoir lists more than 200 Inuit names, every single member of the Smith Sound tribe who’d become Henson’s friends, and more. They include Akatingwah, Henson’s Inuit lover, and Ahnaukaq, their son (although he didn’t identify them as such).

In 1986, Harvard explorer and neurologist Dr. Allen Counter, intrigued by rumors of Henson’s descendants, journeyed to Greenland. His questions about “kulknocktooki” or “dark-skinned people” led him to an ancient man in a remote village.

Through an interpreter, the man joyously greeted Dr. Counter, who was Black, “You must be a Henson. You’ve come to find me.” He was Ahnaukaq Henson, age 80, who now had five sons and 22 grandchildren.

Ahnaukaq insisted that Dr. Counter also visit a good friend and “cousin” who lived 90 miles north. When Dr. Counter arrived, a light-skinned Inuit named Kali also greeted him, “Hello! You must be a Henson.” He, of course, was Robert Peary’s illegitimate son.

In 1987, Dr. Counter arranged for Kali, Anaukaq, and several of their children and grandchildren to visit the United States. They met many of their American relatives in what Dr. Counter called the “North Pole Family Reunion.”

That same year, Dr. Counter successfully petitioned President Reagan to move Matthew Henson’s remains to Arlington National Cemetery near Admiral Peary’s. The ceremony took place with full military honors.

Dr. Counter addressed Matthew Henson’s descendants and admirers, saying:

We are assembled here today to right a tragic wrong, to right the record. Welcome home, Matt Henson, to the company of your friend Robert Peary. Welcome home to a new day in America. Welcome home, brother.

In 1991, Dr. Counter published North Pole Legacy: Black, White, and Eskimo about his odyssey.

In 2000, National Geographic posthumously awarded Henson the Hubbard Medal he should have received in 1909.

Historians still question whether Henson and Peary actually reached their goal. Unlike the South Pole, the geographic North Pole is in the middle of an ocean. It can only be traversed when frozen in winter, but dangerous ice flows continually alter the route.

According to Henson’s memoir, Peary charted their location with a sextant and announced they’d reached the Pole. But based on their journals and modern equipment, most historians believe they fell short.

But there’s no doubt Matthew Henson, the son of Black sharecroppers, was, at age 43, the first American to stand atop the world.

Though not exactly a Later Bloomer, he deserves recognition for all he surmounted and discovered to become one of the 20th century’s most extraordinary explorers. Many sources now acknowledge him as the “co-discoverer of the North Pole.”

His epitaph longingly echoes the last lines of his memoir,

The lure of the Arctic is tugging at my heart. To me the trail is calling! The old trail, the trail that is always new.

And to this day, the Smith Sound Inuit sing songs and tell stories about Mahri-Pahluk.

Matthew, the Kind One.

(You can comment on this article over on the Later Bloomer Facebook Page.)

Sources

- Matthew Henson’s memoir, A Negro Explorer at the North Pole (1912), is available online for no charge through Project Gutenberg.

- North Pole Legacy: Black, White, and Eskimo by Dr. Allen Counter can be found at Amazon and other book suppliers.

- In 1947, Henson collaborated with Bradley Robinson on Dark Companion, a hard-to-find biography of Henson’s life.

- Robinson’s son maintains MatthewHenson.com. The site looks like it hasn’t been updated recently since several links are broken. But it remains the definitive Internet resource on Matthew Henson’s life. (Opening image via MatthewHenson.com; a free public service provided by Bradley Robinson)