I felt I was not gifted, and I had never understood that I could develop skill, one does not have to be born with it.

Abstract Expressionism. You either love it or you hate it.

It was America’s first internationally-recognized art style. It put New York City on the map. Some thought it was genius, others thought it trash.

Jackson Pollock, flinging paint across a canvas on the floor, was its poster child.

But it almost derailed the creative impulse of Melissa Zink (1932-2009), one of the most original artists of our time.

Melissa attended Swarthmore College, the University of Chicago, and The Kansas City Art Institute, an amazing achievement for a woman of her era.

You’d expect with those credentials she’d be a household name, another Georgia O’Keeffe, but she couldn’t relate to the dominant artistic style of 1950s.

“I don’t know how we all lived through abstract expressionism,” she said later. She loved classical art and her instructors at The Kansas City Art Institute denigrated her efforts.

So Melissa turned her back on art.

A few years earlier, she’d married businessman Bill Howell. For the next decade or so, she devoted herself to raising their daughter Mallery and running their business, a custom-framing shop in Kansas City.

Melissa prepared other people’s art for display, but submerged her own longings.

By 1970, Melissa’s frustration boiled to the surface. She convinced Bill to move to southwestern Colorado, where she opened a needlework shop. “I had never been an outside person. But…there was freedom there in a way I’d never known it. Without a well-structured plan, I felt that this was a move that would change my life.”

It did. Bill had neither understood nor encouraged her artistic yearnings. The marriage came to an end.

Odd Scenes in Clay

In 1975, at age 43, Melissa married Nelson Zink, a gifted psychotherapist fourteen years her junior. They moved to New Mexico and settled near Taos.

One evening Nelson asked her, “What do you want to do with your life?”

Melissa couldn’t answer directly. She had to pull the covers over her head. “I want to be an artist,” she whispered.

Nelson, a modern Renaissance man, had discovered clay beds near their house and taught himself to create and fire pots. He asked Melissa if she’d like to try. She couldn’t make a perfect coiled vessel, so she fashioned a series of little clay heads. “I think you’re on to something,” Nelson said.

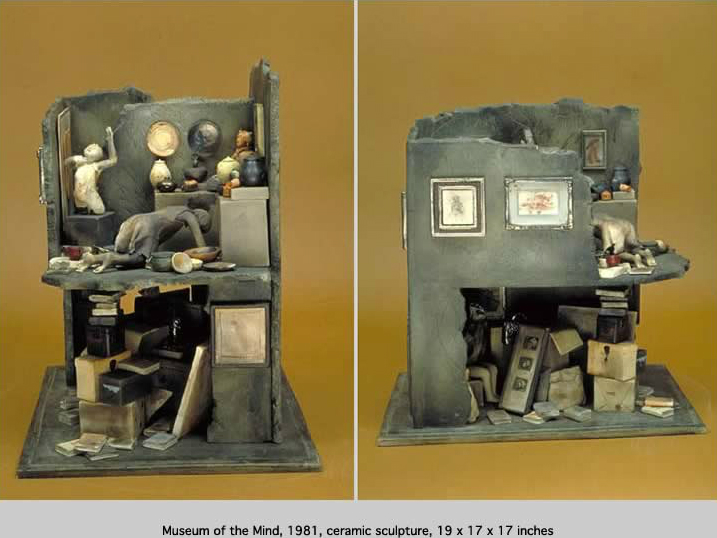

With that tiny bit of encouragement, I started making odd scenes in clay.

“Odd scenes” doesn’t begin to describe Melissa’s three-dimensional stories. Here are some titles:

- Autobiography of An Eccentric (1980)

- A Private Shrine (1980)

- A Fin de Siecle Drama Induced by a Surfeit of Chocolates and French Novels (1981)

- My favorite, Museum of the Mind (1981), pictured above.

- Virginia Woolf, Myth and Metaphor (1987)

[Update March 2014: I’m sad to report that Stephen Parks passed away late last year and the gallery’s site has been removed, so I can no longer link to these works.]

Miners and Explorers

Melissa went on to create in paint, mixed media, and bronze.

I divide artists into two categories, miners and explorers. The miners go deeper and deeper into a fairly narrow vein of subjects and techniques, while the explorers are looking for new and exciting ways to express themselves. I’m definitely an explorer.

In 1993, long-time friends Stephen Parks and his wife Joni opened Parks Gallery in Taos to honor and house Melissa’s works. I’m currently on location attending a writing retreat with Jen Louden and was able to visit Parks Gallery and chat with Stephen.

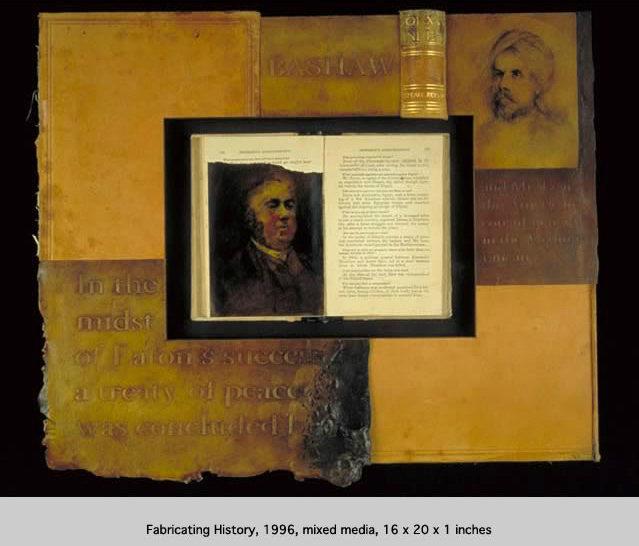

The Beauty of Books

Although not so obvious from these examples, Melissa’s passion for books and the literary life drove her artistic expression.

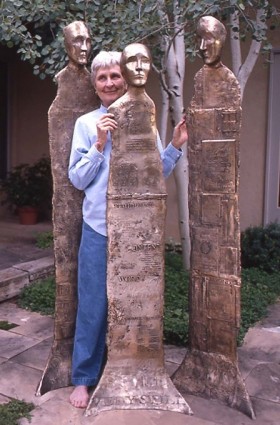

In the post image at the beginning, Melissa poses with “The Guardians,” executed in bronze a few years before her death. They are titled Chamberlain of Letters, Minister of Words, and Book Warden, a testament to the undying power and delight of the printed word.

I viewed the back of the sculptures. They’re embossed with what looks like an infinity of dictionaries and illuminated manuscripts layered upon each other. Melissa used a special technique to make her own stamps.

Everything I find most beautiful and moving is in some way connected to books.

In 2000, Melissa represented New Mexico in the From the States exhibition at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C.

A year later, she received the New Mexico Governor’s award for Achievement in the Arts.

Melissa left us in 2009 at age 77. From the time she embraced her calling in her 40s, for the next 35 years, Stephen Parks says, “There were never enough hours.”

Like many of us, Melissa Zink incubated and experimented until the time was right. And one day, mark my word, she’ll be a household name.

Remember, what’s in style may not be your style. Keep going with your dreams.

Do you consider yourself a miner, an explorer, or something of both?

Sources

- The Parks Gallery (many thanks to Stephen Parks for permission to use these images)

[Update March 2014: I’m sad to report that Stephen Parks passed away late last year and the gallery’s site has been removed. Here’s an older version, however.] - Much gratitude to Lisa Firke for bringing Melissa to my attention!