“The man is not wholly evil—he has a Thesaurus in his cabin.” (Captain Hook as described by J. M. Barrie in Peter Pan)

At 14, he went to university and by age 19 he’d earned his medical degree. (You might call him a Georgian-era Doogie Howser.)

He went on to teach physiology at the University of London, helped found Manchester Medical School, invented a new type of slide rule, designed a pocket chess board, and arguably invented the first movie camera.

But perhaps his greatest accomplishment was a list.

Maybe you’ve heard of it?

Roget’s Thesaurus.

I can’t write in my house, I take a hotel room and ask them to take everything off the walls so there’s me, the Bible, Roget’s Thesaurus and some good, dry sherry and I’m at work by 6:30. ~Maya Angelou

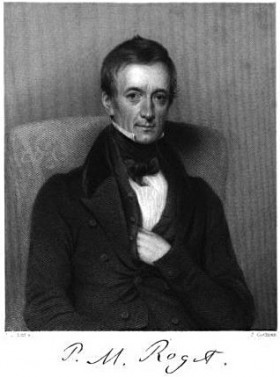

Strictly speaking, Peter Mark Roget (1779-1869) doesn’t qualify as a late bloomer.

He was a precocious scholar who began his career while in his teens and went on to pursue several positions in medicine and science.

At age 55, Roget wrote a paper entitled “Explanation of an optical deception in the appearance of the spokes of a wheel when seen through vertical apertures.” In it, he described an odd phenomena—that if a person observes a moving wheel through a series of vertical slits (such as a picket fence), the spokes of the wheel seem to curve. Roget devised a shutter-and-aperture device to study this observation. Many consider it a movie camera prototype.

But it was when Roget retired from medicine in 1840 to pursue his true passion—the classification of words through their synonyms and antonyms—that he achieved his ultimate accomplishment. Roget published his Thesaurus in 1853, at age 74.

Roget’s Thesaurus is so comprehensive and useful, that during the 1960s, ’70s and even the ’80s, two reference volumes could be found on every student bookshelf in America: Webster’s Dictionary and Roget’s Thesaurus.

His list was his life’s work.

His list—Roget’s Thesaurus—has helped millions of people across more than a hundred years.

And it may have saved his life.

A Man Beset by Heartbreak

Although obviously accomplished, Roget experienced overwhelming heartbreak in his life. His father died of tuberculosis when he was four. His mother suffered from paranoia, often accusing the servants of plotting against her. Both Roget’s sister and daughter experienced mental breakdowns. His wife, 16 years his junior, died of cancer at age 38. His favorite uncle and surrogate father slit his own throat, while Roget fought to take the knife from him.

To cope with this litany of tragedy, Roget developed an abhorrence of dirt and disorder and an obsession with lists and counting. He showed the hallmarks of what we today call obsessive-compulsive disorder, not to mention depression. No wonder.

And so, in his biography of Roget (The Man Who Made Lists), Joshua Kendall concludes that the Thesaurus did much more for Roget than for its millions of users across the centuries. The ultimate book of lists became his salvation and “it enabled Roget to live a vibrant life in the face of overwhelming loss, anxiety, and despair.”

Twenty-eight editions of the Thesaurus were published during Roget’s lifetime. He died at age 90.

Obsession served him well.

And Roget’s “later blooming” has served all of us well, too.

Later Bloomer Lessons from Peter Mark Roget

- Never discount your passion because it seems too strange or too simple.

Roget’s lists have benefitted millions. - We each have a personal battle that defines us. Later blooming involves unearthing a creative, individual strategy that increasingly leads us beyond coping into the sublime.

Sources

- The Man Who Made Lists: Love, Death, Madness, and the Creation of Roget’s Thesaurus

by Joshua Kendall

- New York Times book review of Joshua Kendall’s The Man Who Made Lists by Thomas Mallon

- “The Myth of Persistence of Vision Revisited,” Journal of Film and Video, Vol. 45, No. 1 (Spring 1993): 3-12