Today starts the long July 4th “weekend” celebrating America’s successful colonial rebellion. Did you know that one of our Founding Fathers was a late bloomer?

He started his adult life as an indentured servant at 12 (the official “age of reason” back then). But his master physically abused him and, at age 17, he defaulted on his apprenticeship and became a fugitive. He landed in Philadelphia with a price on his head and started using pen names, including Richard Saunders.

His life took several more twists, and at age 70, he became the oldest signer of the Declaration of Independence. Have you guessed the identity of this late-blooming Founding Father?

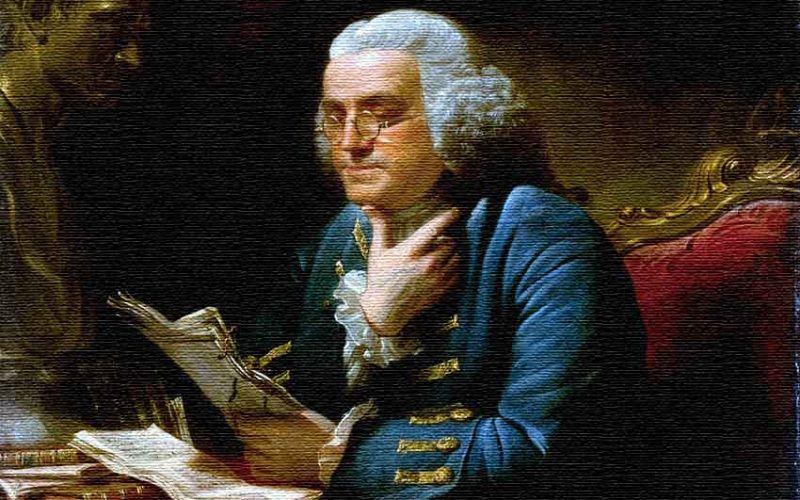

It’s Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), of course.

Like Peter Roget, he was a polymath: printer, statesman, activist, inventor, and diplomat. By 26, he was a best-selling author.

Yet if we look at the timing of Ben’s greatest passions and achievements, he might also qualify as a late bloomer. In his 40s, he sold his business and embarked on a life of science and service. In his 70s, he helped birth a nation.

Silence Dogood, Fugitive

Ben was the youngest of fifteen sons born in Boston to Josiah Franklin, a Puritan immigrant. Josiah marked Ben for the clergy, but could only afford to give him two years schooling. Ben’s formal education ended when he was 10.

Josiah employed him in the family candle-making shop. “I disliked the trade,” Ben said, “and had a strong inclination for the sea.” To keep him from running off, Ben was apprenticed at age 12 to his brother James, a printer.

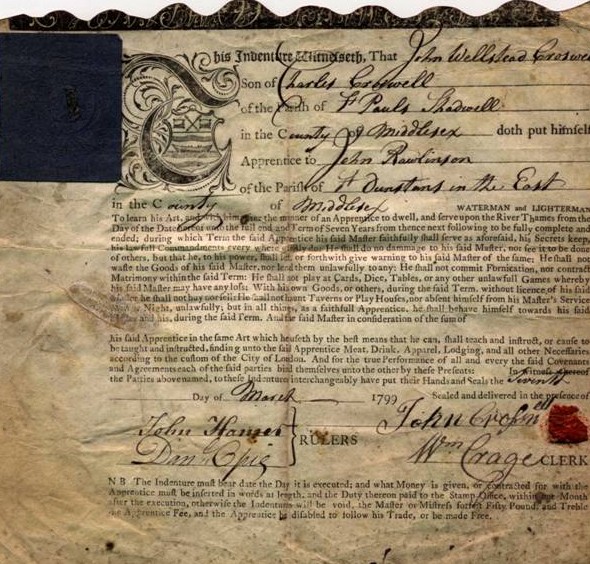

Apprenticeship involved signing an indenture contract drafted in duplicate, then separated along a jagged edge resembling teeth (hence its name). Authenticity could be confirmed by joining the two edges. Today we consider legally binding a pre-teen outrageous, but Ben had no choice. He signed away the next nine years of his life to learn a trade.

Ben loved books, so printing was perfect for him. He learned quickly, but his brother “expected the same services from me as he would from another.” This included Ben’s acceptance of regular beatings.

From ages 12 to 15, Ben undertook an enviable program of self-development. He educated himself by reading the books he printed and taught himself persuasive writing by imitating the articles. He sought to improve his character by cultivating thirteen virtues and practicing them on a rotating basis for the rest of his life. The modern FranklinCovey planning system models part of its line on Ben’s self-improvement program.

When Ben was 15, his brother founded the Colonies’ first independent newspaper. By then Ben had become a skilled writer, but James refused to publish his submissions.

So Ben created his first alter ego, Mrs. Silence Dogood, a middle-aged widow who sent the newspaper letters lampooning Colonial life. She became the readers’ favorite, and even received a few marriage proposals.

When James discovered the ruse, his anger and jealousy finally boiled over. One too many beatings later, Ben defaulted on his indenture and became a fugitive.

Poor Richard Makes Good

Ben landed in Philadelphia at age 17 and obtained work as a printer, eventually taking over The Pennsylvania Gazette. In 1732, at 26, he created another alter ego, Richard Saunders, an impoverished hen-pecked husband. Ben’s lively writing made Poor Richard’s Almanack a yearly best seller.

Ben denied being Poor Richard, but no one was fooled and it became part of his legend. PBS calls Ben the “First American Humorist.” Here are some of his famous one-liners:

- Fish and visitors stink after three days.

- Blessed is he who expects nothing, for he shall never be disappointed.

- In this world nothing is certain but death and taxes.

Ben sold his printing press after thirty years and pursued the intellectual life he missed at age 10 when his father pulled him out of school.

And what a life! Some of Ben’s “retirement” activities include:

- Experimenting in electricity, including identifying lightning as a source.

- Founding the Colonies’ first post office, fire department, and lending library.

- Inventing bifocals, the lightning rod, and the Franklin stove.

In 1753, when he was 47, England awarded him the Copley Gold Medal (a kind of early Nobel prize) for his work with electricity. He became an international celebrity.

Ben later moved to London to champion Colonial interests. This self-educated printer was invited to join the British Royal Society, awarded honorary degrees at Oxford, Cambridge, and St. Andrews, and welcomed into the homes of England’s leading intellectuals.

Unfortunately, even Ben’s wit, intellect, and diplomacy couldn’t win over the British government. He returned to Philadelphia when events made war between England and her Colonies inevitable.

The Elder Statesman

In 1775, Ben was elected to the Second Continental Congress and became part of a secret committee that drafted the Declaration of Independence.

Historian Richard B. Morris has identified seven men as key “founding fathers” of the United States, so designated for their various contributions to American independence. Look at their ages in 1776:

- Alexander Hamilton, age 21

- James Madison, age 25

- John Jay, age 31

- Thomas Jefferson, age 33

- John Adams, age 41

- George Washington, age 44

- Benjamin Franklin, age 70

Immediately after signing the Declaration of Independence, Ben sailed to France, an ambassador to the court of Louis XVI and a traitor to the government of George III. Had he been overtaken at sea, he would have been hung.

He secured France’s military and financial aid for his fledgling United States, and in 1783, negotiated The Treaty of Paris, which officially ended the Revolutionary War. Ben returned home a hero and signed the United States Constitution in 1787 at age 81.

Ben Franklin was a fifth-grade dropout and runaway apprentice who wrote his way to fame and fortune, followed his passion into a lightning storm, and birthed a nation.

Perhaps remembering his own time under indentured servitude, he championed freedom until the end. A year before his death at age 84, he penned an anti-slavery treatise and became president of Pennsylvania’s first abolition society.

Calling Benjamin Franklin a late bloomer might be pushing it. But he since he considered himself a life-long learner, I don’t think he’d disagree!

Late-Blooming Wisdom from Ben Franklin

(I’ll let Poor Richard speak for himself):

- “What you would seem to be, be really.”

- “When you’re finished changing, you’re finished.”

Sources

- PBS’s fascinating Ben Franklin site

- Opening Image: Franklin by David Martin (1767)